There is a tendency, when talking about TV shows, to get caught up in the same old anecdotes and stock opinions.

Star Trek: The Next Generation only got good with Season 3. Panorama was briefly interesting in 1957 with its spaghetti harvest April Fools, and again that time when Dimbleby sat there like a twat when no films would run. Catchphrase is reduced to Mr. Chips having a wank next to a snake.

It’s the same with sitcoms. Hancock is all about armfuls of blood and reading off cue cards. Are You Being Served? is entirely centred on Mrs. Slocombe’s minge. The Office invented a whole new way of making comedy.1 So it is with Fawlty Towers, which has its own set of anecdotes and origin stories, all endlessly repeated over the years until nobody bothers to question them.

So let’s question one of them, shall we?

* * *

Still, even I have to admit: if you want to tell the history of Fawlty Towers, it is obligatory to take a trip back to Torquay, May 1970.

The details of this encounter have been endlessly described. The short version: the Monty Python team check into the Gleneagles hotel, as somewhere to stay while they shoot location material for Series 2.2 The hotel’s proprietor is a certain Donald William Sinclair, who proceeded to be endlessly awful to everyone.

“He was the rudest man I’ve ever met. He was wonderful. And all the other Pythons wouldn’t put up with it. They moved out and went to stay in the Imperial, which was a lot better. And he was so extraordinarily rude. I mean, one day, we were all at dinner, and Terry Gilliam was eating as Americans do. That is to say, they cut the meat like this, and then they cut it all up, and then they put the knife there, pick the fork up in the right hand, and spear the meat. And he was walking by and he looked down at Terry and this look of astonishment crossed his face, and he said: ‘We don’t eat like that in this country!'”

John Cleese, Fawlty Towers: The Complete Collection DVD interview

With it being easy for these things to grow in the telling over the years, it’s worth noting that Michael Palin’s contemporary diaries back up Cleese:

“Mr Sinclair, the proprietor, seemed to view us from the start as a colossal inconvenience, and when we arrived back from Brixham, at 12.30, having watched the night filming, he just stood and looked at us with a look of self-righteous resentment, of tacit accusation, that I had not seen since my father waited up for me fifteen years ago. Graham tentatively asked for a brandy – the idea was dismissed, and that night, our first in Torquay, we decided to move out of the Gleneagles.”

Michael Palin Diaries 1969-1979, Monday May 11th, Torquay

While Palin, Jones and Chapman left the next day, John Cleese was fascinated by this ridiculous character, and decided to stay.3 Connie Booth joined him shortly afterwards… and they both sat back and watched. Five years later, on the 19th September 1975, Fawlty Towers aired, and a comedy series people will still be watching a century later was born.4

But it wasn’t our first glimpse of the character that would eventually become Basil Fawlty. That would come on the 30th May 19715, in a little show called Doctor at Large.

* * *

I say “little”, but as we shall see, that isn’t exactly an apt description.

Doctor at Large was the second incarnation of the series of Doctor sitcoms, inspired by Richard Gordon’s series of comic medical novels, and broadcast on ITV. 6 John Cleese was involved with the show from the very beginning – in fact, with Graham Chapman, he wrote the very first episode of its first incarnation in 1969, Doctor in the House. For those of you who might think this was just filler work in-between writing Python, Cleese paints a very different picture in his autobiography:

Doctor at Large was the second incarnation of the series of Doctor sitcoms, inspired by Richard Gordon’s series of comic medical novels, and broadcast on ITV. 6 John Cleese was involved with the show from the very beginning – in fact, with Graham Chapman, he wrote the very first episode of its first incarnation in 1969, Doctor in the House. For those of you who might think this was just filler work in-between writing Python, Cleese paints a very different picture in his autobiography:

“It’s not that hard to get the hang of writing sketches, and by now Gra and I were capable of writing a very decent TV half-hour. (In fact, during this whole period the best script we did was a pilot for Humphrey Barclay based on Richard Gordon’s Doctor in the House; with Gra’s medical-student background it proved surprisingly easy to create a funny and believable programme, and it gave rise to a long-running series.)”

John Cleese, “So, Anyway…”, p. 381-2

It did indeed give rise to a long-running series. Across all the LWT incarnations of the series – Doctor at Large, Doctor in Charge, Doctor at Sea, and Doctor on the Go7 – the show racked up 137 episodes, between 1969 and 1977.

This stands in sharp contrast to Fawlty Towers itself, which famously managed just twelve. Doctor at Large alone had a full 29 episodes broadcast between February and September of 1971, weekly on Sunday nights, without a single break. This situation already gives the lie to the idea that the only way British sitcoms have been made over the years is six episodes at a time. You don’t have to look very far to find out endless examples which break that “rule”.8

Still, the 29 weekly episodes without a break of Doctor at Large is unusual.9 And this number of episodes lets Doctor at Large play with a rather unusual structure. Unlike many sitcoms where the situation stays the same from episode to episode, the life of our hero Michael Upton – played with a beautiful naive charm by Barry Evans – is constantly shifting, as he struggles to find his niche as a newly-qualified junior doctor.

In the first episode, he’s still at his old teaching hospital St Swithin’s, working in outpatients; by the third, he’s working as a GP in a less-than-salubrious area of London – a situation which could have made for a sitcom in itself, especially with the amazing Arthur Lowe as Dr. Maxwell. But five episodes later, he’s out on his ear, Arthur Lowe leaves the series, and Upton decides to go and visit his parents. Come episode nine, he’s back working at St Swithin’s. Episode 10? He’s going for a job in an upmarket private practice… but that only sticks for three episodes. You get the picture.

It sounds like a mess, but in fact it works extremely well, and gives the series a really unusual, unpredictable feel. The idea that all sitcoms put their toys back in the box at the end of each episode exactly where they found them is sometimes overstated, but a series’ central situation shifting in this manner is an unusual thing indeed. You don’t even get the comforting familiarity of the standing sets, like with Doctor in the House – the base of the series keeps changing.

To be clear, this is not bad writing on the series’ part, where it can’t quite figure out what it wants to be: it accurately reflects the life of a young doctor, as Upton and his friends try to figure out what career path they want to take. There is a real point to the chaos. Indeed, the series does have a central situation: it’s just that the situation is Michael Upton’s life, not any particular dusty GP’s surgery.

This was the situation John Cleese found the series in, when he returned to writing for the show – solo, this time – after nearly two years away. It seems that, in true John Cleese style, he started writing for the show again due to a particular financial incentive:

“I’d lost some money in an investment – I put some money into a gym and set a man up, and about three months later he died. Most extraordinary! I’d lost quite a bit of money on that, so I wrote some Doctor in the House shows.”

John Cleese, “Life Before and After Monty Python”, p. 86

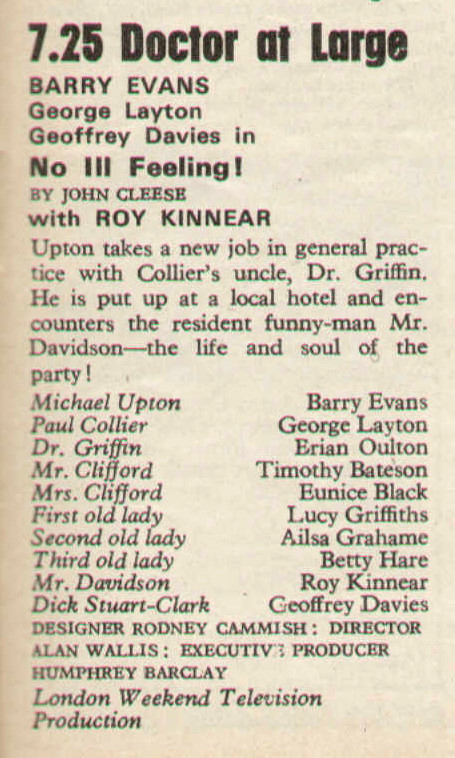

But the show’s current ever-shifting situation suited John Cleese down to the ground. He wanted to write something which featured that mad hotelier he had met the previous year. Maybe this would have been a difficult episode to justify in a tight six-part series, but Doctor at Large was flitting around across many different scenarios: one of them could easily be a hotel. And so episode 14 of the series – titled No Ill Feeling!10 – ostensibly starts a six episode arc11 set in a GP surgery in Harrow, run by Dr Griffin. (Who is a hypochondriac, because the show had to do that joke at some point, obviously.) But the real meat of the episode comes from Upton staying in a local hotel, the Bella Vista.

A hotel run not by a Mr. Fawlty, or even by a Mr. Sinclair… but by the stressed, inattentive, waspish Mr. Clifford.

* * *

Ah, Mr. Clifford. Let’s meet him, then, as Upton attempts to check in.

At first, the above is a bit of a culture shock, if directly compared to Fawlty Towers. Mr. Clifford – played by versatile character actor Timothy Bateson – has very little of the sheer gangling energy that Cleese brought to Basil Fawlty. There isn’t going to be any goose-stepping climax to this story, nor is he going to faint dramatically. In fact, quick movements of any kind are RIGHT OUT.

But if you look closer, there is plenty in the above scene which could immediately fit into Cleese’s masterwork. It’s very easy to imagine a version of A Touch of Class which started with a variation of the above scene. Mr. Clifford’s opening “Yes?” is as much Basil Fawlty as anything John Cleese and Connie Booth ever wrote.

Of course, there are differences. Obviously, Doctor at Large‘s point of view character is Dr. Upton; therefore, it’s entirely acceptable for Mr. Clifford to wander in and out of the scene in a way Basil never would. In Fawlty Towers, we’d have to follow Basil as he went in and out. The unseen wife nagging from the back room also feels a bit of stereotyping which Fawlty Towers would add a lot more depth to; Basil might be scared of Sybil, but he would always get his revenge… once she was out of earshot.

When Mrs. Clifford finally appears (“We do ask our guests to be prompt for meals!”), we get another sign of the differences between the two shows. In Fawlty Towers, it’s Basil who is physically large and imposing, and Sybil who is smaller. In No Ill Feeling!, it’s entirely the other way around. In fact, this is exactly how it was in real life with the Sinclairs:

“Now, he was quite small, physically, and Mrs. Sinclair was sizable. So it was more obviously the sort of henpecked husband situation. By reversing it, because I couldn’t be small, obviously, and Pru is not very tall, we kind of took it away a little bit from the more obvious aspects of the henpecked husband.”

John Cleese, Fawlty Towers: The Complete Collection DVD interview

Sometimes, real life is just too much of a cliche.

Perhaps the biggest difference between Mr. Clifford and Basil Fawlty in the above scene, though, is how Mr. Clifford reacts to Upton’s revelation that he is a doctor. This would have immediately sent Basil into one of his painfully fawning routines, as in The Psychiatrist. Mr. Clifford, however, couldn’t give less of a flying one, and is merely angry he has to fill in his booking form again. Everyone who wants to stay in his hotel is a menace as far as Mr. Clifford is concerned. Basil, on the other hand, has a whole raft of people he desperately wants to impress. “I’m terribly sorry, we hadn’t been told!”

As the episode progresses, things go from bad to worse between Dr. Upton and Mr. Clifford, culminating in a disagreement about kippers in the dining room. You have to assume that John Cleese finds the cadence of the word “kipper” funny; you also have to assume that he finds the idea of people carrying them around for no reason equally as amusing, as this happens in both No Ill Feeling!, and of course The Kipper and the Corpse:

So the similarities between Mr. Clifford and Basil Fawlty are there for all to see. But ultimately, unlike Basil, Mr. Clifford doesn’t come across as especially neurotic. He’s rude, certainly, and as ill-suited to running a hotel as Basil is. But the depths of Basil Fawlty aren’t anywhere to be found. There just isn’t time to really scrape back the layers of the character. Not because you couldn’t do it in a single episode – of course you could. Look at all the class resentment A Touch of Class manages to deal with. But Doctor at Large has other things on its mind.

Because the dirty secret of No Ill Feeling! – at least until you watch it – is that for all people talk about our proto-Basil, there really is very little of him in the show. The main plot is given over to another monster altogether. And as far as I’m concerned, he’s somebody far more unpleasant than Basil Fawlty ever was. But nobody ever really talks about him.

More on that horrific individual next time.

With thanks to Gary Rodger and Tilt Araiza of The Sitcom Club podcast for the TV Times archive. Also thanks to Tanya Jones and Ian Symes for notes and feedback.

It didn’t. ↩

Michael Palin’s diaries, two days into the shoot: “We drove out to the location and spent the rest of the afternoon playing football dressed as gynaecologists.” ↩

Interestingly, according to Palin’s diaries, Eric Idle stayed on as well, a detail which is often lost. It makes you wonder what an Idle take on Donald Sinclair would have been like. ↩

For the best and most complete account of the nightmare which was the Gleneagles under Donald Sinclair, I recommend Graham McCann’s excellent book, simply titled Fawlty Towers. As well as pulling together all the various newspaper reports over the years, it also includes information from some original interviews conducted by the author, which haven’t been seen anywhere else. ↩

The TX date of the episode we are going to discuss seems to have got rather confused over the years. Kim Howard Johnson’s tome Life Before and After Python claims the episode aired in “early 1973”; The Rough Guide to Cult TV gives the date 3rd February 1973. This is a mistake, though, and clearly refers to a repeat run done at this time. The episode definitely first aired in 1971, not only according to the TV Times, but also the TV listings section of The Times, which would have picked up most instances of last-minute rescheduling. ↩

They should have adapted the book Doctor in the Nude. ↩

I am deliberately leaving out Doctor Down Under and Doctor at the Top, but I feel duty-bound to mention them in this footnote because otherwise somebody will say “What about Doctor Down Under and Doctor at the Top?”, and then I shall have to punch them in the fact and point out that I specifically said the LWT incarnations of the show.

That should, of course, be “punch them in the face”, but on reflection I think I prefer the typo. ↩

Drop the Dead Donkey had 10 episodes in its first series, and never did a six episode run. Last of the Summer Wine likewise rarely did six episode runs – and they were also often in batches of 10 or 11 in its later years. And Series 3 of Dad’s Army in 1969 was 14 episodes in length – and that’s on top of six more episodes broadcast earlier in the year. I could go on, but I have an article to write. ↩

UPDATE (30/11/19): This article originally said that I was unaware of any UK sitcom which had a series longer than 29 episodes. So thanks to David Brunt, who has pointed out that the first series of Bootsie and Snudge in 1960-61 had a total of 40 episodes. ↩

Both Life Before and After Monty Python and The Rough Guide to Cult TV give the episode title incorrectly as No Ill Feelings. This is the problem with relying on what other people have written about a subject rather than actually watching it for yourself. ↩

Yes, I said “arc”. In an LWT audience sitcom from 1971. They weren’t invented by HBO, you know. ↩