Short version: along with people far cleverer than me, recently I’ve been involved in rescuing an old BBC Micro game from oblivion, after 25 years of it not being playable.

The long version follows.

* * *

In 1993, there was only one thing I wanted, as I played on my old, faithful BBC Master.1 And that was to own something else.

Oh, don’t get me wrong. I loved my BBC Master. I spent a large proportion of my life on it. But, y’know, I was 12. On one side was my friend who owned a Sega Mega Drive. On the other was all the Acorn magazines… filled with coverage of the increasingly wonderful Acorn Archimedes. I would have done anything to own either of them.

I begged. Believe me, I begged. No dice. It’s difficult to argue our family was poor – we lived in a detached house in a nice area of Nottingham – but that detached house was where the money had gone. There wasn’t a huge amount of cash to splash around, least of all on computers.

Of course, we had a room full of Archimedes machines at school. I’d rush to get onto the A5000, and stare at Mode 28, 640 x 480 in 256 colors… and then when I got home, I’d stare sadly at Mode 2, 160 x 256 in, erm, 8 colours.2 I’d go round to my friend’s house – he was rich – and I’d stare at the amazing games I was missing out on: Chocks Away, or the Lemmings port. And I’d stare wistfully at that beautiful GUI, and scowl at my BBC Master’s command line.

I was so jealous, in fact, that I tried to write my own GUI for my BBC Master, based on the Archie’s RISC OS. I got as far as colouring the screen a dithered grey pattern, and drawing a rectangle at the bottom to represent RISC OS’s Icon bar. I then drew a square to represent an icon… and at that point realised I was about as out of my depth as it was possible for a human being to be. My magnum opus of a GUI sadly remained unfinished.

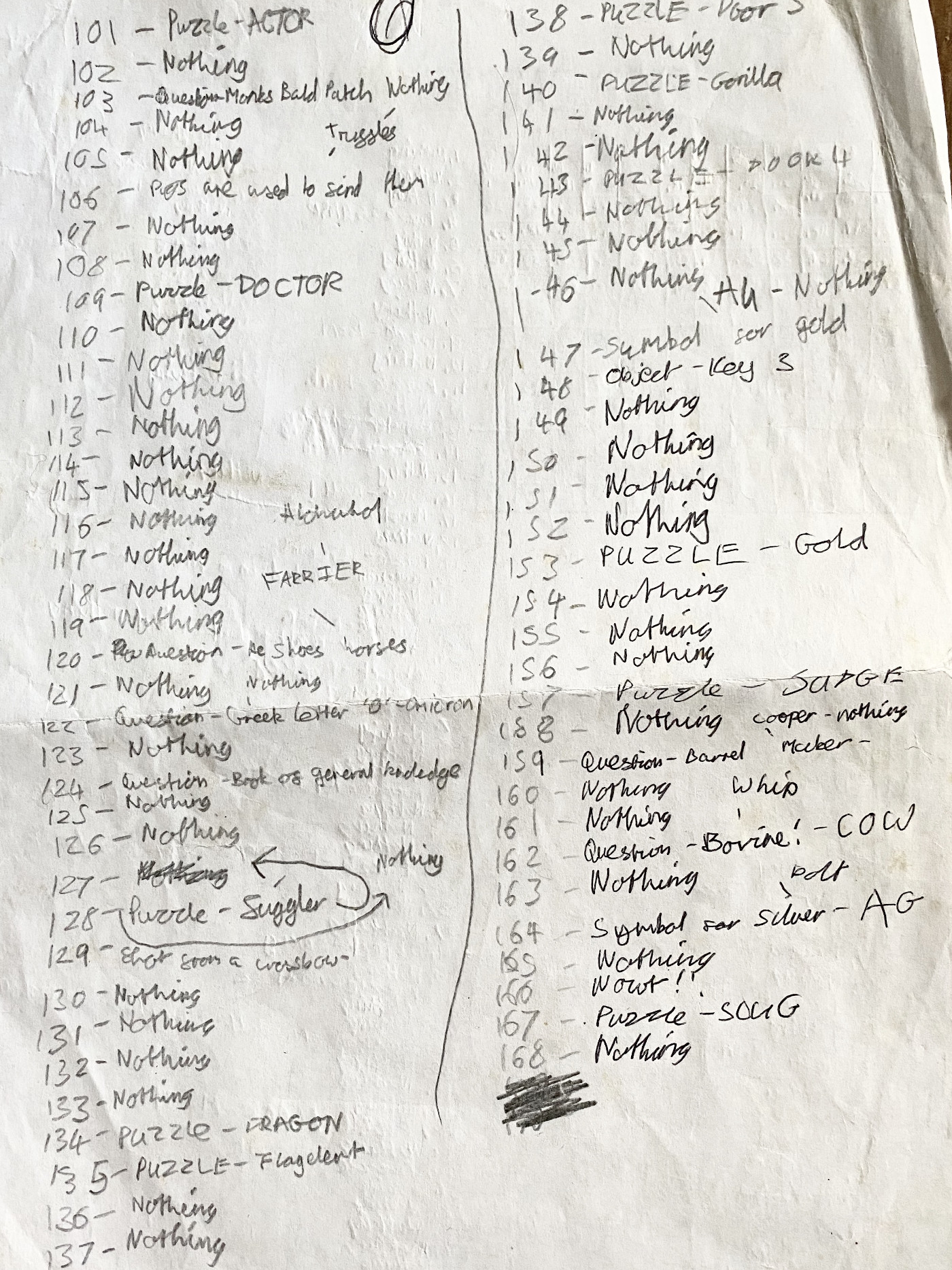

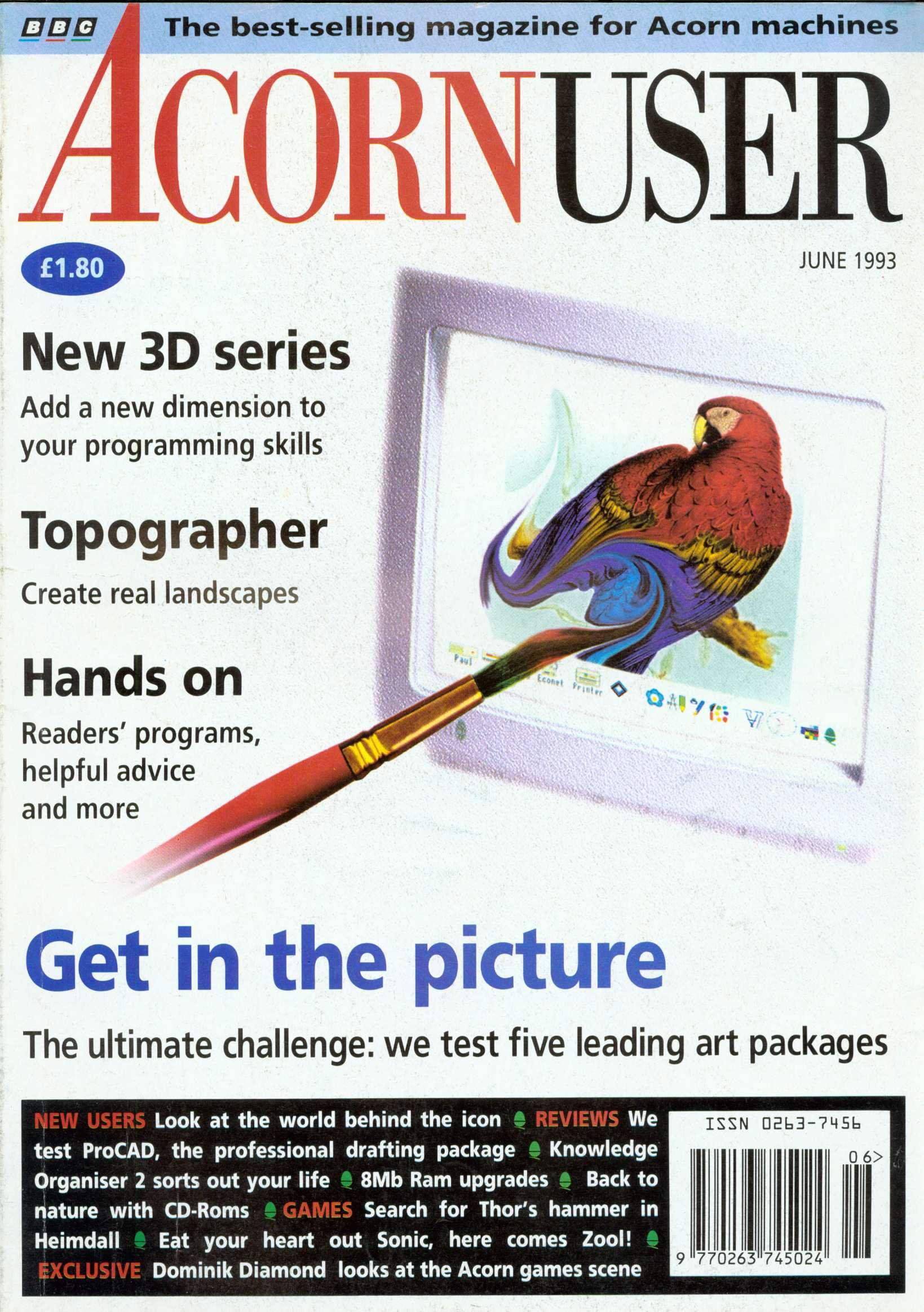

Still, time was ticking, and I was stuck. My favourite magazine Acorn User had been reducing their 8-bit content for years by this point. Between May and June 1993, any mention of the BBC Micro or Master was quietly removed from the cover.

And not coincidentally, the June issue featured this as its lead story:

Our family just couldn’t afford to upgrade to an Archimedes. But coverage and software releases for my BBC Master were rapidly screaming to a halt. Being an ungrateful kid, I made my displeasure known. The fact that I had a roof over my head and was clothed and fed clearly meant nothing. My computer situation was dire, and that’s all that mattered.

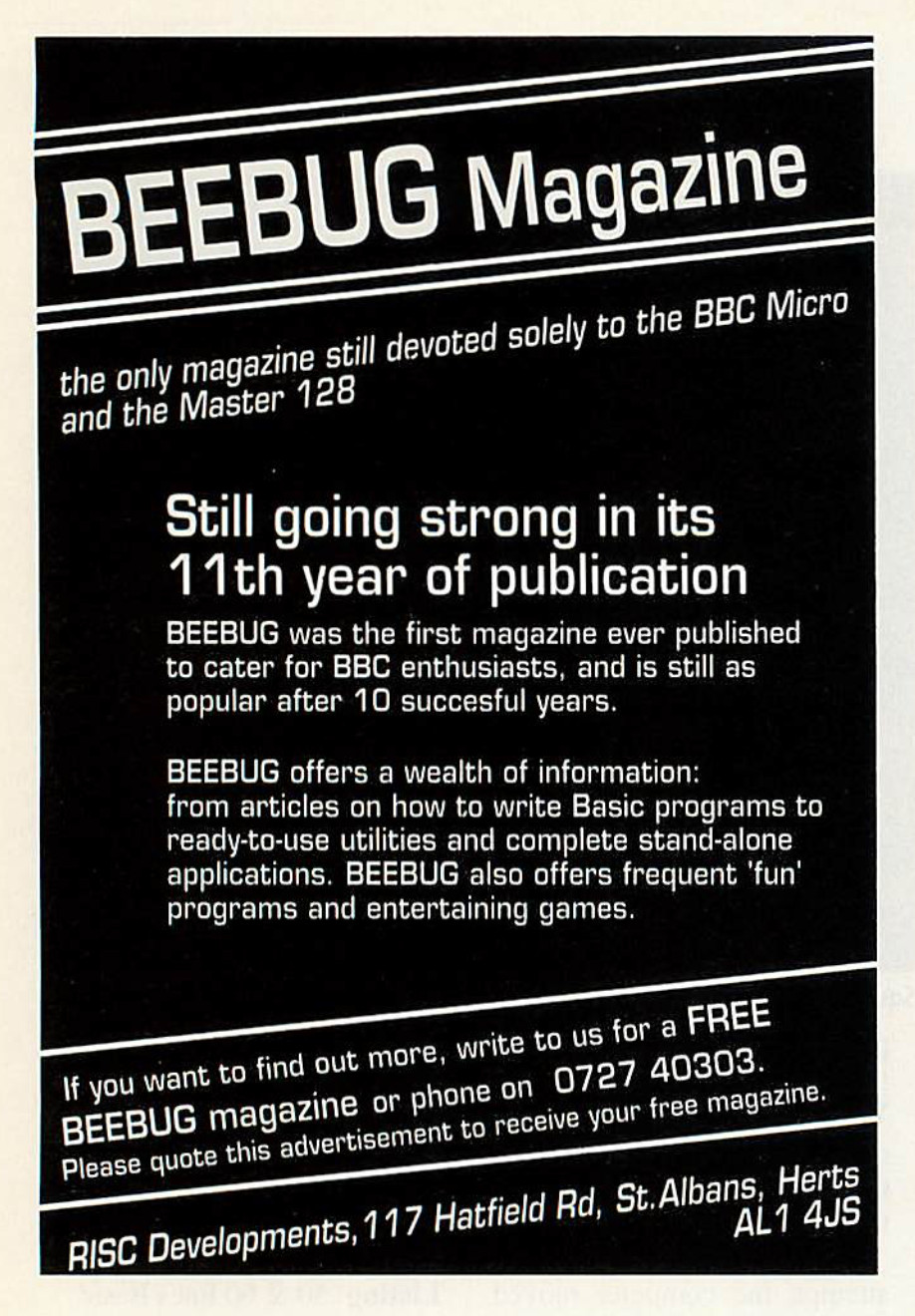

But then I espied my saviour. Ironically, it was in the pages of Acorn User.

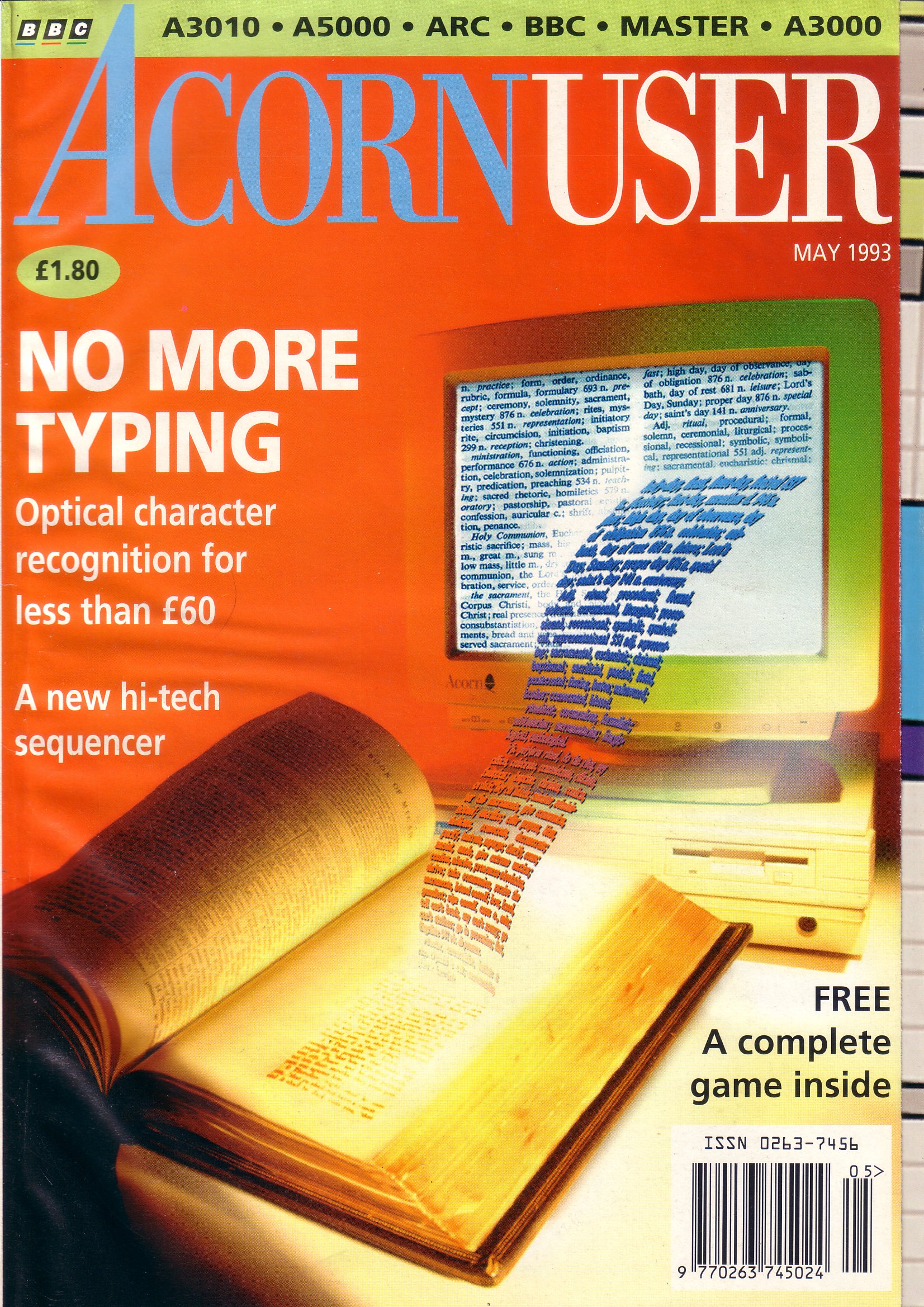

BEEBUG had been going since the BBC Micro had first launched, but our family had never subscribed to it. But how could I turn this offer down? It would feature coverage of the computer I actually owned, rather than I wished I owned. And my first issue wouldn’t even cost me anything – a crucial factor. I wouldn’t even need to beg my parents. I immediately sent off for my sample copy.

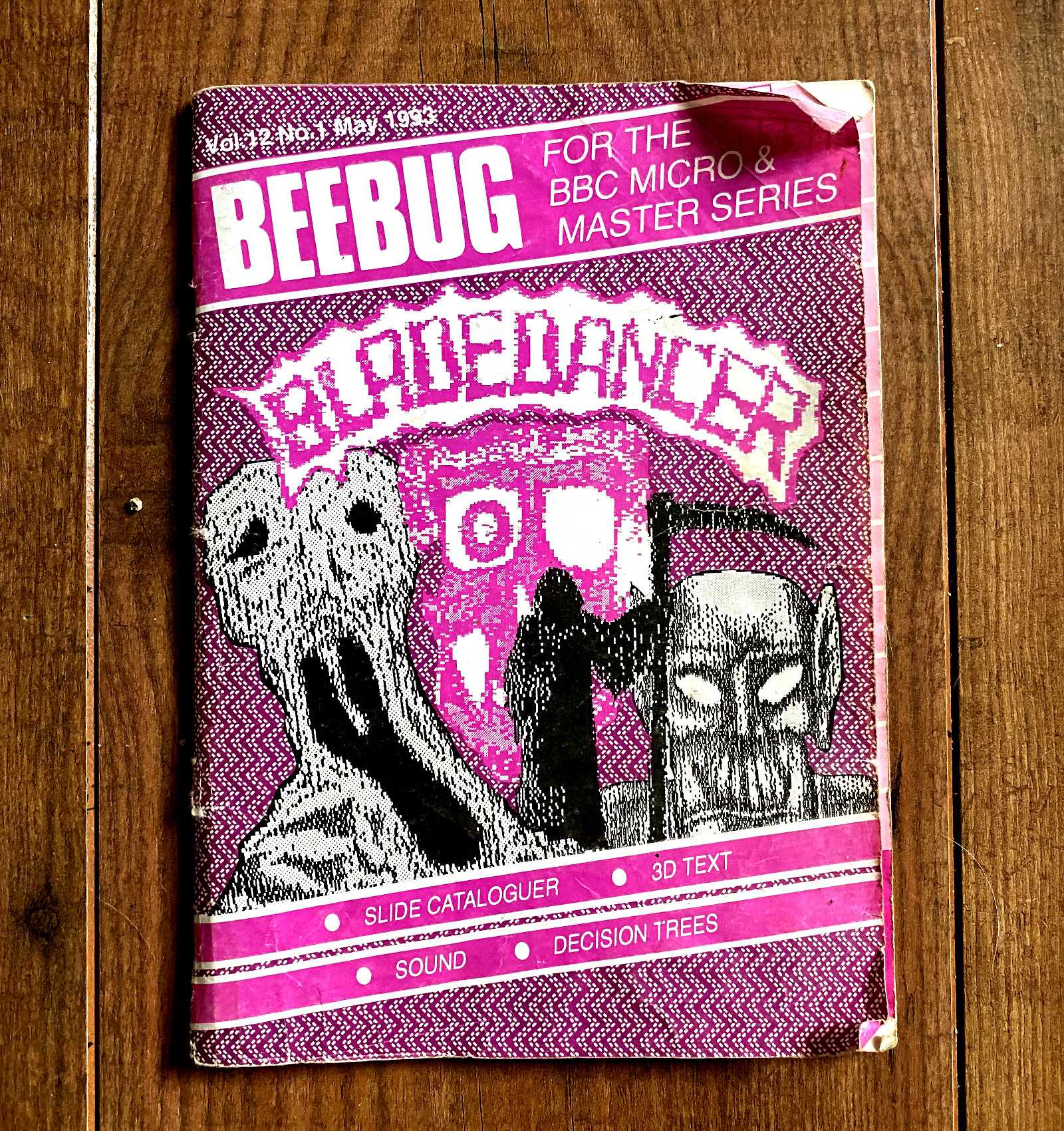

I still have what was sent back to me. Oooh, that cover looks interesting, doesn’t it?

I quickly opened it up. The first page: Editor’s Jottings. What comforting missive will I find, from “the only magazine still devoted solely to the BBC Micro and the Master 128”?

“Readers will not be unaware that 8-bit technology has now been overtaken by 32-bit developments of which Acorn’s Archimedes range is a prime example. Many users with a BBC Micro have already converted to an Archimedes system, and it is clear today, that with a very few honourable exceptions, virtually all commercial activity is concentrated on the Archimedes range. Other magazines have completely or largely given up on the BBC Micro, and most hardware and software developers have long since concentrated on the Archimedes range for their new products.”

Uh-oh.

“This has been reflected in the readership of BEEBUG, which has declined steadily since the heyday of the BBC Micro seven or eight years ago now. We have fewer subscribers than was once the case, but despite this, we have maintained BEEBUG at 64 pages for a considerable time. However, the point has been reached where we can no longer sustain this size of magazine, and thus with effect from this issue, we will be producing BEEBUG to 56 pages.”

Well, that’s not the end of the world. That’s still far more than Acorn User‘s Beeb content in 1993, after all.

“There is one further consequence of what I have had to tell you. With the current and projected circulation of BEEBUG, we do not believe that it will be viable to continue with publication beyond April 1994.”

Oh bollocks. There was just no way to win with this one. I was doomed to irrelevance, and there was nothing I could do about it.

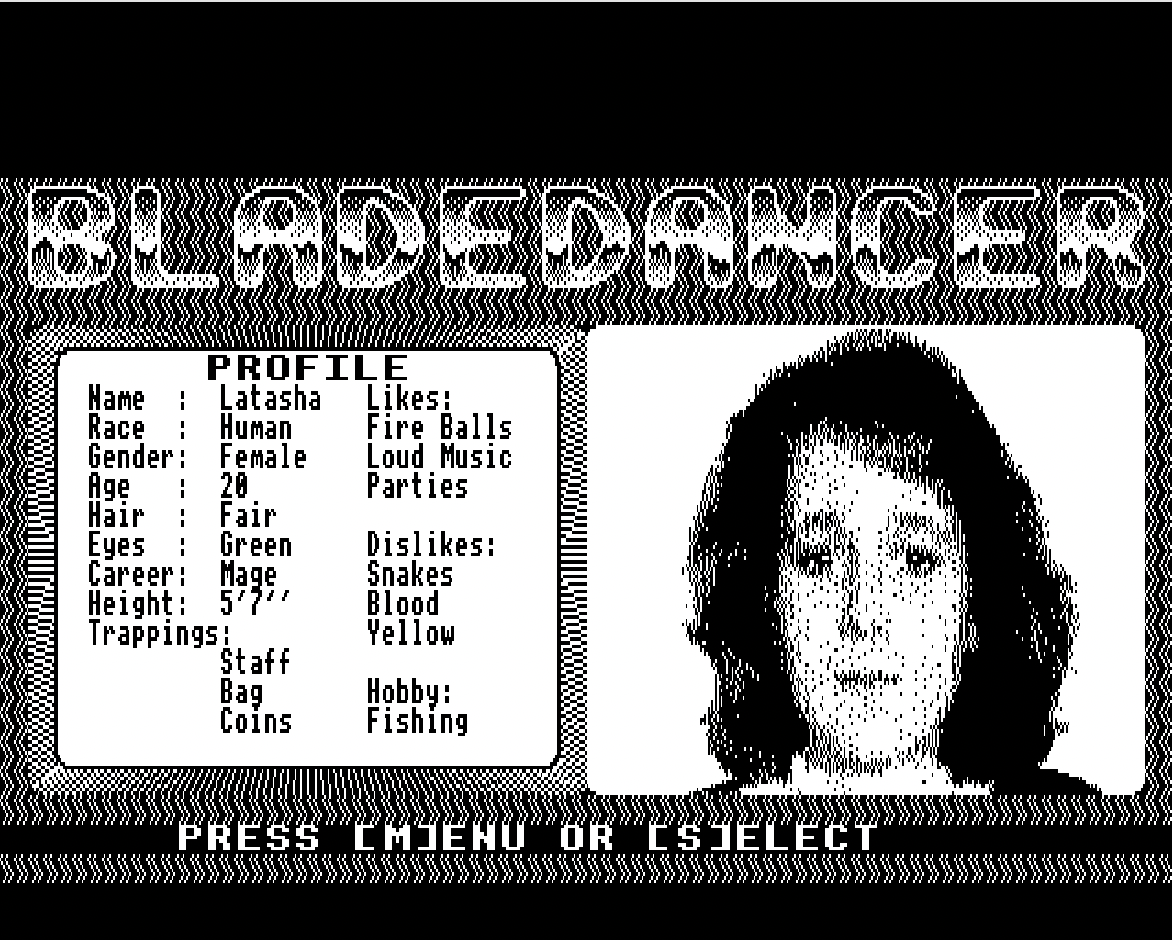

Never mind. Back to that intriguing looking cover. I’d never heard of Bladedancer3 before. A new game for the Beeb? It looked like nothing else I’d ever seen for the platform before. Let’s take a look at that review inside.4

“A new game for the BBC series of computers is rare enough and, no matter what the content, we all have to be pleased to see a new company taking the machines seriously – Omicron Technologies are taking their work very seriously.

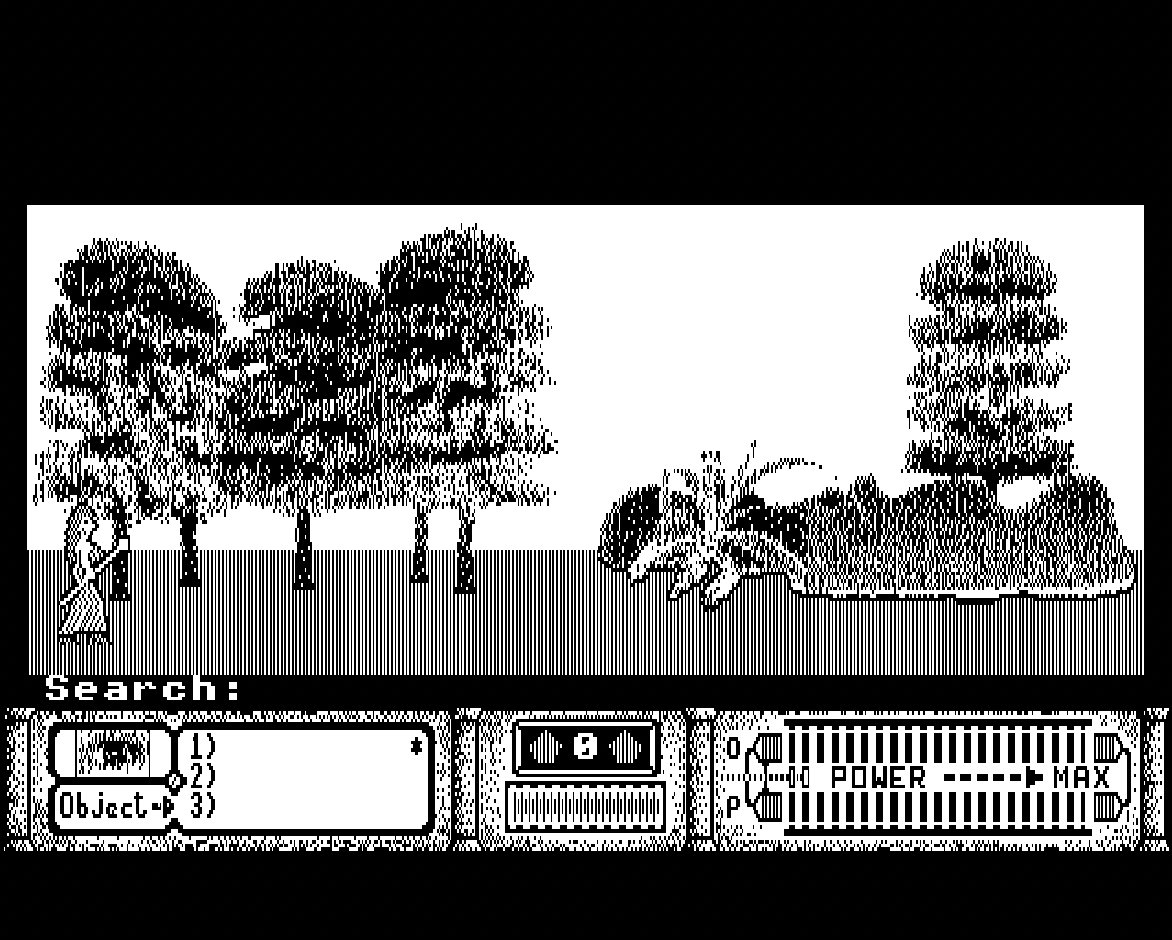

Let’s look at what we’re dealing with here. This isn’t another shoot ’em up variation, it’s not Pacman or platforms, this is a full blown role playing adventure. Not only that, we’re talking graphics digitised from video and sampled sound, though you do need sideways RAM to get all the goodies.

Ooooh! And my BBC Master has sideways RAM as standard, we’re all good there. But is it actually worth the money?

“Of its type this package is at least very good. Of its type on the BBC nothing I have seen comes close and it’s very sensibly priced.”

That was it. OK, so my inept GUI experiments were doomed to failure. But here was somebody who knew what they were doing, creating a game which took my BBC Master, and made it look… well, not like an Archimedes. But certainly look more advanced than anything else I owned. Come on, digitised graphics! That’s the most exciting thing ever!

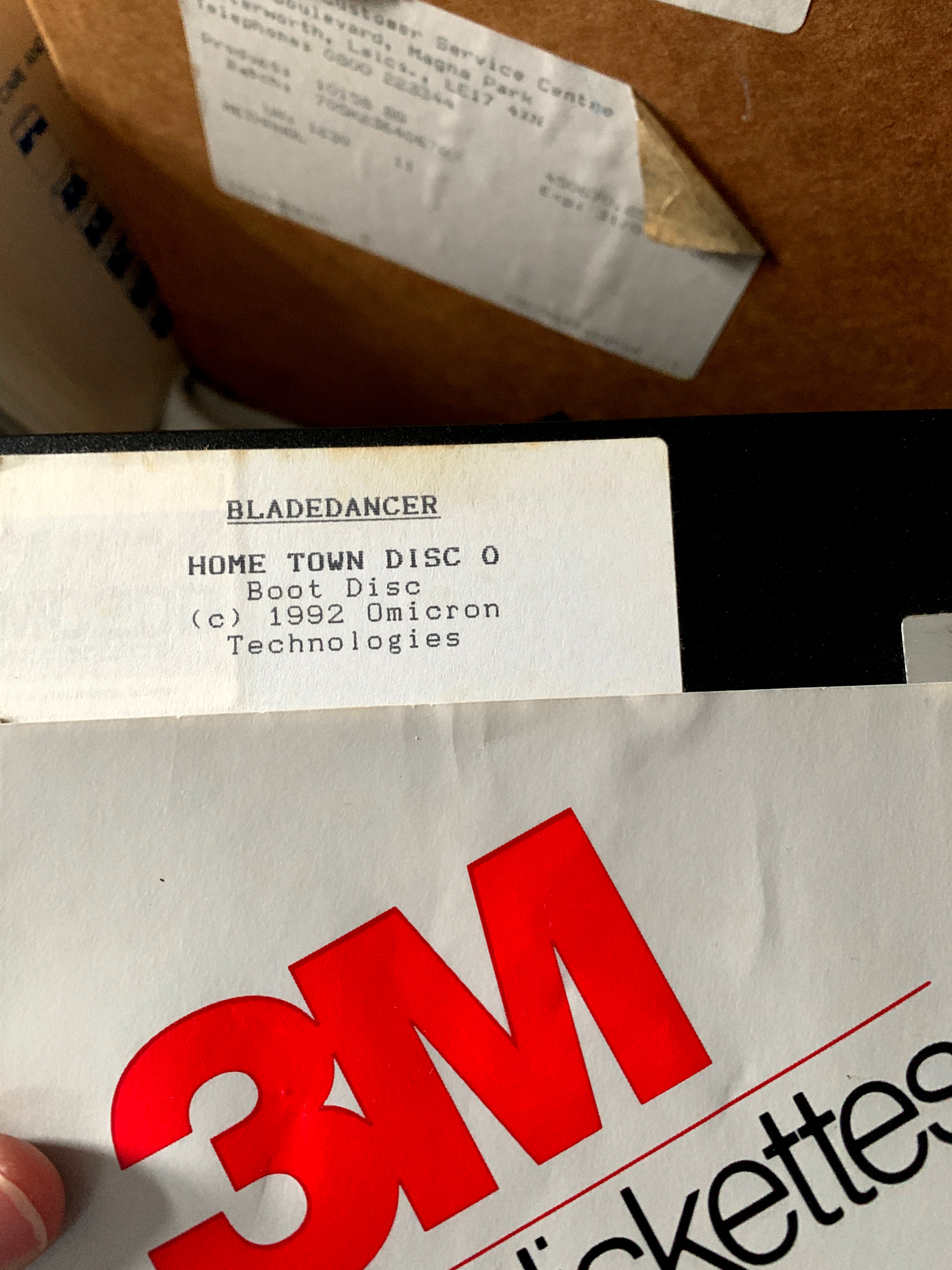

So, I ordered it. Well, my gut tells me I probably asked for it for my birthday – I didn’t have the money the rest of the year to spend on this stuff, and my birthday was the same month as this issue of BEEBUG. Regardless of where I scrounged the money from, I sat back and awaited the arrival of the 5-disc epic.

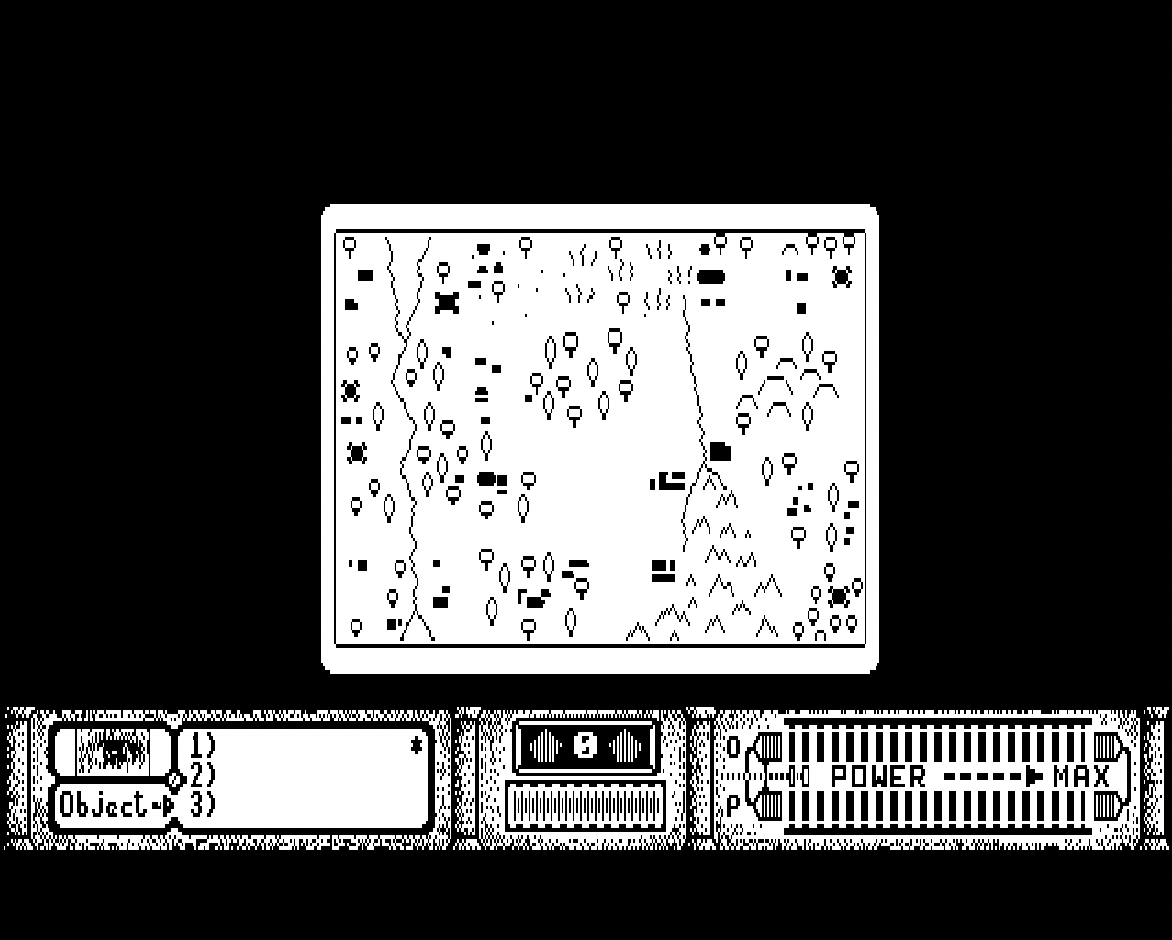

And this is where I think I’m supposed to tell you that the game arrived, it was everything I hoped for, and it cheered me up just when I most needed it. Sadly, real life doesn’t always work like that. The aim of the game was to find nine pieces of pentagram; I don’t think I even found one. After the initial thrill of having a game which looked like nothing else I owned, it soon became clear that it was just a little too annoying to play, at least for my temperament at the time. Only being able to travel to adjacent locations made the game really, really slow.5

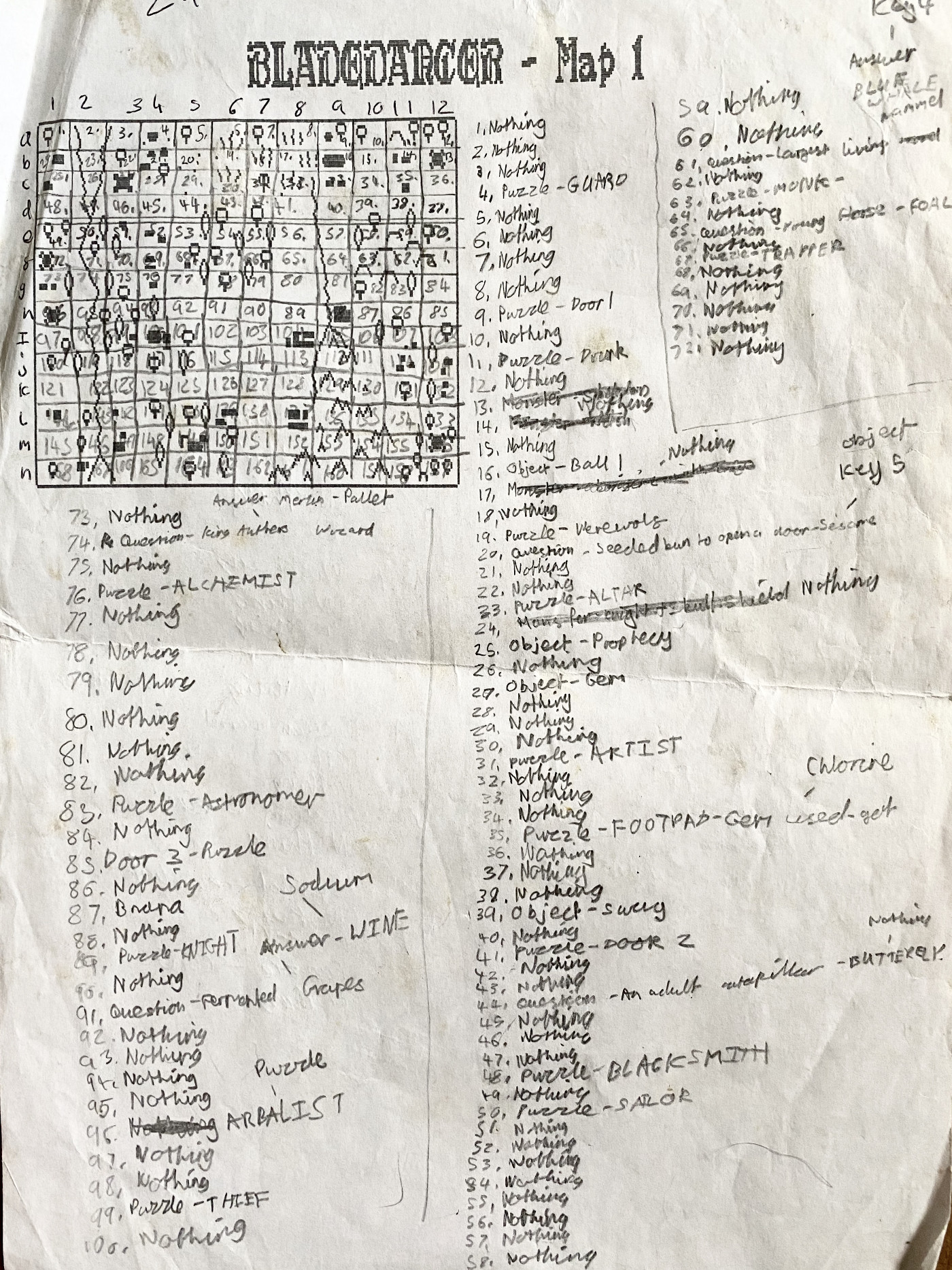

I did, however, manage to create a map of the first world. By the time I’d spent the time and effort doing that, I couldn’t bear to actually go through and try to complete it. The game sat gathering dust.

* * *

Still, there was a happy ending to all my computer-related woes. The next year, my Dad died.6

Sometimes, death completely screws over a family’s finances. Luckily, it did the exact opposite for us. All of a sudden, while we didn’t exactly have money to throw around, things were a little less tight. And I got my Mum to agree that if I paid for it weekly from my paper round, I could have a brand new Acorn Risc PC.

That leap – from 8-bit to 32-bit, from a BBC Master to a Risc PC – is probably the single biggest leap in computing power I’ll ever experience in one go. I vividly remember waiting for it to arrive one morning, and the huge van pulling up outside. I will never be as excited about a computer again for as long as I live. Finally, I had everything I wanted. (Well, apart from my Dad, but what are you going to do?)

So, my BBC Master languished. And continued to languish, as I made my way through the dying fag end of RISC OS as a commercial venture, played with Windows for a while, and eventually moved onto a Mac. And my relationship with computers slowly changed over the years too. At one point, it seemed obvious that despite my early problems, I’d probably go into programming of some kind of description as a career. I even attempted a Computer Science degree. These days, I direct TV channels for a living, and some crudely hacked PHP is about my limit.

Over those years, I sat at the very periphery of the Acorn retro scene. I spent a fair bit of time on Stairway to Hell, gazing at maps for Labyrinth. I always made sure I had a Beeb emulator handy, and played a fair few games on it. I wrote the odd thing like this. But I was never a part of the community. I just hung around, peering in occasionally.

However, I knew enough that something rather puzzling soon became apparent. When I searched for that old Bladedancer game I once had, in order to give it another go, it seemed to be missing. Every single other Beeb game I’d played was freely available to download, even Blue Ribbon releases like Joey, which I was unaccountably fond of. But Bladedancer appeared to be AWOL.

At first, merely AWOL… but slowly, it began to gather a near mythical status. How could it not? A 5-disc epic, one of the last contemporary commercial releases of a game for the BBC Micro, and yet nobody seemed to have a copy. There was enough evidence of it that nobody seriously postulated that it never existed – but as time went on, it became more and more peculiar. Why did nobody have this sodding game, when nearly every other release of note had been carefully preserved and made available?

There were occasional stirrings, however. As recently as 2017, no lesser person than the actual author of Bladedancer turned up on the main Beeb retro forum, and offered the discs for preservation. Everyone – including me, silently lurking – waited with bated breath. He soon seemed to go cold on the idea, and never posted the discs to the relevant people. It was infuriating. One of the last contemporary commercial game releases for the BBC Micro, and it endlessly seemed to slip from the community’s grasp.

At this point, you are surely all thinking the obvious. I clearly had the discs in my possession. Why the hell didn’t I step forward earlier, rather than waiting around? The answer is simple: because I’d assumed the discs were long corrupt. Even when I was using my BBC Master full time back in the 90s, I was getting plenty of dreaded Disc Fault 18 errors. Those Bladedancer discs were stuck in my dusty bedroom in Nottingham until the early 2010s, then unceremoniously shoved into a dusty wardrobe in London. And frankly, I hadn’t taken particularly good care of them even back in 1993. I honestly thought the chances of getting anything off them at all were remote.

Still, it was worth a try. And early this year, I was forced to go through that wardrobe, in preparation for a house move. So with a bit of rooting round… oh, hello.

It was peculiar, seeing them again. In the intervening years, they’d turned from just a normal bunch of BBC Micro discs, to something that had become something of a holy grail when it came to Beeb preservation efforts.

They also represent something of a delicious irony. Over the years, my interests had been moving away from computing, and more towards television. For years, I’d read about people rescuing old television programmes, the master tapes long since wiped by the channel that commissioned them. I’d go to events like the BFI’s Missing Believed Wiped, and watch newly-recovered television programmes, and hear the stories of film cans being stuck in an attic for years. I’d become a true archive TV geek.

And here was my very own Missing Believed Wiped moment. But not a lost TV programme, from my adult love of old television; instead, it was a long lost computer game, from my childhood love of 8-bit Acorn machines. These things never turn out how you expect. But then, nobody plans to find a load of missing TV in their garage, just as nobody plans to have one of the few remaining copies of an old BBC Micro game in existence. It just happens.

It’s what you do once you find out exactly what you have which is key.

Dodgy tales abound when it comes to missing TV programmes. People who have the only extant copies of material… and refuse to let it be preserved. Then there’s tales of money changing hands, or people demanding certain things happen before they’ll hand the material over. Of course, exactly the same things happen with software preservation too. Indeed, as detailed in this forum post, it once happened with Bladedancer; it appeared on eBay, was sold to someone who wanted to preserve it, only for the seller to wind up refusing to send the goods.

I always said I’d never do that if I ever had the fortune to be in this situation. Here was my chance to prove it. The only thing I cared about was getting the material into the right hands; I just did not have the right kit to scrape the data off those discs into something that you could easily use with an emulator. Moreover, if the discs were difficult to read – as I was sure they would be – then I just didn’t have the technical knowledge to rescue them. I wasn’t interested in shoving them on eBay and getting paid – I just wanted the game to be preserved, and everyone to have a chance of playing it again.

So I turned to my old friend Dave Jeffery, who is far more a part of the Beeb retro scene than I am. He put me in touch with Arcadian over on the Stardot forums, and he put me in touch with Bill Carr to do the actual ripping. I quickly sent the discs off – after a minor scare where I thought I’d lost one of the discs7 – and then all I could do is sit back and wait.

I have to be honest: I didn’t hold out much hope. Not because of the people involved – I trusted them completely. But after 25 years, would the discs still be readable?

* * *

Well, they were. I mean come on, I admit that at the top of this article. No false jeopardy here.

Still, what I find most surprising is how easily those discs actually read. I thought there was a high chance they wouldn’t read at all, and if they did read, it would be through some kind of major recovery voodoo. Turns out that wasn’t the case at all. Word came back quickly from Bill Carr; three of the five discs read fine first time round, there was a single bad sector on one of the other discs, and the remaining disc had 4 data CRC errors… which disappeared entirely when the disc was read again.

Which means that after well over two decades of the game not being available… you can now play it again. The multi-disc nature of the beast means it’s a little trickier than most games to play in-browser, but follow the instructions carefully, and it works. Or just use your favourite BBC Micro emulator.

Which just leads me to reflect on the pure chance that lead us to this. If our family had been able to afford an Archimedes when I wanted one, I never would have even been aware of Bladedancer, let alone bought it. No wonder the game was so rare; most people who gave a damn about this stuff had probably stopped buying BBC Micro games by this point.

It also gives me some satisfaction that I’ve finally been able to give something back to the Acorn community in this regard. If helping to rescue what had become a true holy grail of missing BBC Micro software is the only thing I ever do for it, then I’m more than happy with that. Of a world that gave me so much pleasure over the years, I’ve finally been useful in return.

And the community is where that game resides now. I might write a little more about Bladedancer in the future – I have a special connection to it, after all. But what’s brilliant about this kind of thing is how it truly belongs to everybody now. I’m not the right person to write a walkthrough, or do a Let’s Play. There are so many other people who can take the game, and do something special with it.

Still… do you fancy a bit of a head start? Fine. Here’s my map of World 1, which I made right back in 1993.

Good luck.

Note for those who aren’t Acorn freaks: the BBC Master was the successor to the BBC Micro. It was still often found in schools, and was the one which looked like a BBC Micro, but with a numeric keypad. ↩

No, not 16. I don’t want to hear about any of your “flashing colours” nonsense. ↩

It’s at this point that we have to deal with the inevitable: just how should this game be capitalised? At various points, it’s written as Bladedancer, BladeDancer, Blade Dancer, and – most commonly – BLADEDANCER. After much consideration, I’ve plumped for Bladedancer in this article, as it just strikes me as the most readable option. If you want to argue for something else, by all means feel free. Erm, over there, please. No, a bit further. That’s it, thank you. ↩

For a full copy of the review in BEEBUG, see this forum post. ↩

I also never really figured out the combat, but I blame myself for that one. ↩

As a sign of just how important computers were in our family, our BBC Master got mentioned in my Dad’s funeral service. The celebrant – Dad was devoutly non-religious – mentioned that my Dad had set up a new computer for him and me “to share”. This was bollocks – he’d set up a brand new BBC Master in his room so we wouldn’t have to share, and I got the old one – and I spent the rest of the service impotently fuming about the error. ↩

Seriously, how annoying would that have been? “Here’s most of long-lost game Bladedancer…” Luckily, I found the missing disc in another box. ↩