Part One • Part Two • Part Three • Part Four • Part Five

It’s the 8th April 1970 at 9pm, and BBC1, BBC2 and ITV are all transmitting the same thing. It is, of course, a Party Political Broadcast: this one by the Labour Party, titled “What’s at Stake?”. It seemed pretty normal, on the face of it. I mean, the promise of MP trio George Brown, Anthony Crosland, and Robert Mellish might sound a bit too exciting, but I’m sure the country could keep itself under control.

The very next day, the papers were in uproar.

The Daily Mail is typical, in its piece “Complaints on Labour broadcast”:

“Both the BBC and ITV had callers last night complaining that the first one or two minutes of the Labour Party’s political broadcasting contained subliminal advertising.

The programme had been recorded and the BBC explained: ‘We are not responsible for the content of party political broadcasts, it is entirely up to the parties concerned. We provide the facilities.'”

Uh-oh. So what did Labour have to say about this?

“‘Subliminal advertising?’ said a Labour Party spokesman. ‘No, not really.

What happened was that we opened the programme with an anti-switch off factor to grab people’s interest. It went on for not more than 30 seconds with film shots and some raucous voice saying: ‘We don’t expect you to vote.’

I understand that the complaint is that the words “Labour Tomorrow” appeared twice very quickly, so quickly that they registered on the eye and not the brain.'”

Hmmmmm. Regardless of anything else, I would suggest statements like “registered on the eye and not the brain” are liable to make people more suspicious about what was broadcast, not less.1

Regardless of that, for a while it looked like nothing else would happen. The Daily Telegraph published the following on the 10th April, under “Subliminal advertising by Labour denied”:

“Neither the BBC nor the Independent Television Authority is to take any action over allegations that the Labour party political broadcast on Wednesday contained subliminal advertising.

Both organisations maintained yesterday that no such advertising was included in the programme. They said no action would be taken about complaints from viewers.”

But a week later on the 16th April, the front page of The Times reported the following, under “Investigation on Labour TV film”:

“The Labour Party political broadcast on television which used a quick flash technique and brought claims that subliminal methods were being used is to be investigated by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The men behind the inquiry are Mr. Norris McWhirter and Mr. Ross McWhirter, the publishing twins.”

Oh, hello there. Well, we’ve been avoiding this topic for about as long as is practical. We need to talk about the McWhirters.

* * *

What exactly can you say about Ross and Norris McWhirter? Sports journalists, check. Setting up The Guinness Book of Records, check. Known to kids across the country on Record Breakers, check. And both were known for their various support for right-wing causes, which seemed to grow harder as time went on.2

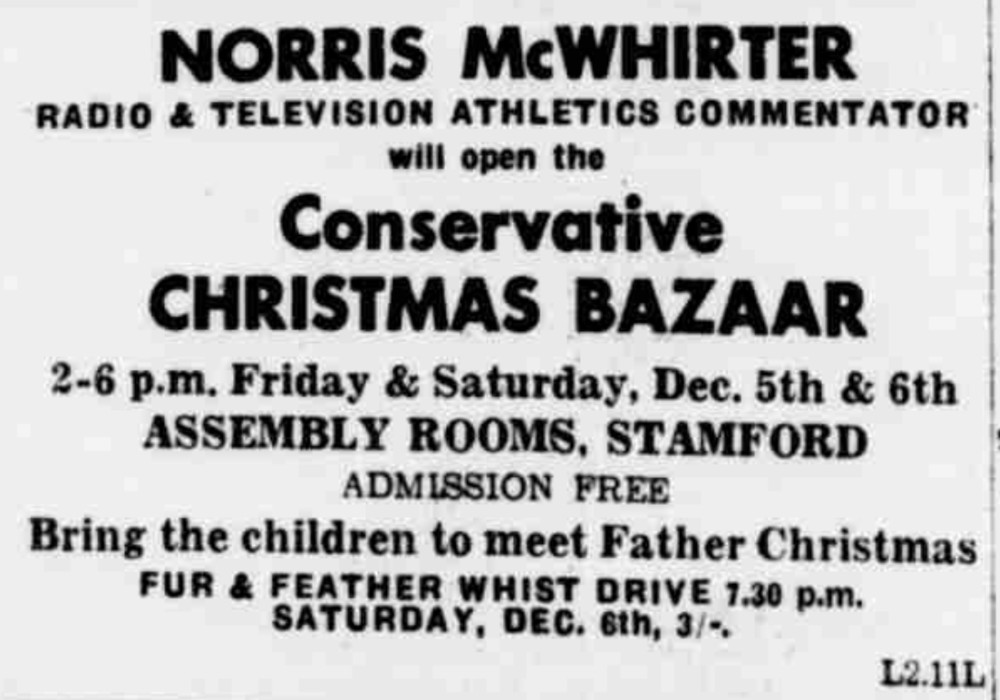

This slightly queasy mix of broadcaster and political agitator is captured by Stuart Jeffries in this Guardian piece, but maybe the below, from 1969, is a more typical representation of their public reputation around the time we’re talking about:

Just to be clear: whatever your opinion on Norris McWhirter, he was not Father Christmas.

More importantly for our purposes: over the first half of the 70s, the twins gained an increasing reputation for litigation. In 1973, when The Brand New Monty Python Bok was undergoing legal review, there was worry about a page featuring a newsletter called “The Bigot”, and a letter from “Col. Sir Harry McWhirter M.C.C.”. The feedback solemnly noted that it “might be construed as suggesting that Mr. Norris McWhirter the well-known litigant, was a racist”. This piece of advice was, of course, duly ignored.

As for why the pair were so litigious: well, we can find out what their publicly stated reasons were, at least. Elsewhere in 1973, Ross McWhirter attempted to put a stop to ITV transmitting what he viewed as an obscene documentary on Andy Warhol.3 In a very sympathetic4 interview he gave Lynda Lee-Potter in the Daily Mail, we get his public defence of such practices:

“I’ve taken a number of actions in the past few years,’ he said yesterday… and they have all had the same stamp on them.

I believe in the law. My hackles rise when I see some flagrant flouting of the law and this is what the IBA were attempting to do.

There is a statute passed by Parliament which simply says that it is the duty of the IBA5 not to transmit anything which is against good taste or likely to be offensive. […]

Why should there be this feeling that television has become such an opiate, such a god that it has become immune from the need to obey the law? I’m not fascinated by power, neither am I a sort of Lord Longford committee man.

Any action I take I take on my own. People often think I am a catspaw for the Festival of Light but I am entirely a one man band. I am part of no pressure group. I form my own judgement and I act.”

This defence of their intentions crops up frequently. If we head back to our Party Political Broadcast, then Ross says something very similar, also published in the Daily Mail, on the 16th April:

“He said last night: ‘We have no political motive in this brainwashing complaint. If it had been the Tories I would have done the same thing.”

In other words: this stuff is never political guv, it’s just about the law. I shall leave whether to believe this or not as an exercise for the reader.

* * *

Right, back to the flash frames. Let’s get into the nitty-gritty of this particular incident. Carrying on with that Daily Mail piece, titled “Did Labour’s TV break the law?”:

“A Labour party spokesman said last night that four of the messages were of one frame and lasted 1/25th of a second each. There were other ‘Labour tomorrow’ slogans – one of four frames and one of eight frames. He added: ‘We understand that 1/50th of a second is the subliminal borderline.’

But Mr James O’Connor, director of the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, which laid down a subliminal code for television, said: “That is nonsense.

‘Such a flash is undoubtedly far too quick for the conscious mind to grasp, but it registers nevertheless. In other words it is quite definitely subliminal.

‘Anything up to three frames, or about one eighth of a second, is not visible to the naked eye.'”

At this point, it’s worth checking exactly what the rules about subliminal messaging were at the time. For that, we need to study The Television Act 1964, which defined the constitution and functions of the Independent Television Authority6, then in overall charge of ITV.

The relevant section is 3(3):

“It shall be the duty of the Authority to satisfy themselves that the programmes broadcast by the Authority do not include, whether in an advertisement or otherwise, any technical device which, by using images of a very brief duration or by any other means, exploits the possibility of conveying a message to, or otherwise influencing the minds of, members of an audience without their being aware, or fully aware, of what has been done.”

Note that this specifically states the rule applies to all material broadcast on an ITA-licensed station, not just advertisements. Or to put it another way: a Party Political Broadcast should indeed be bound by this rule. What it doesn’t give is an exact technical definition of what a subliminal message is; merely “a very brief duration or by any other means”.

The Daily Mail continues:

“Both the BBC and the ITA have a statutory duty to satisfy themselves that no programme includes subliminal material.

A BBC spokesman said: ‘We saw the programme before it went out and saw the message “Labour tomorrow.” We did not see any subliminal messages. That does not mean there were none.”

The ITA said: “We took the view that as the slogan “Labour tomorrow” was clearly seen during the programme, it was not subliminal. We don’t know about any other messages.'”

Predictably, the saga really seems to end before it had even started. There was a brief kerfuffle over the next month, with the focus eventually settling on the next Labour Party Political Broadcast, due to be transmitted on the 4th May: would they repeat their supposed subliminal messaging?

You can get a sense of the appeals court hearing from the Birmingham Evening Mail on 1st May:

“‘Subliminal flashes were envisaged to the human eye,” declared Mr. McWhirter, who appeared in person. ‘I do not know the message they contained.’

Lord Denning, Master of the Rolls, said: ‘Then it does not affect you, does it?’

Mr. McWhirter — Yes, it is evidence that this is a form of brainwashing.

Lord Denning — Even though you do not see it? — Yes.

Lord Justice Widgery said: ‘You say this is an example of the hidden persuaders?’

Mr. McWhirter replied: ‘Yes. I say the Television Act stops this. The conscious mind can both see and hear certain things, but the unconscious mind can take in subordinate matter.’ Mr. McWhirter contended that the previous broadcast had amounted to “undue influence” on the general public.”

But that same day, the Friday before transmission, it all came screaming to a halt. As the Daily Mail reported the next day, under “No to brain-wash claim”:

“An attempt to stop any ‘subliminal advertising’ in next Monday’s Labour Party political broadcast failed in the Appeal Court yesterday.

Mr Ross McWhirter, 44-year-old former athlete and Tory candidate, sought an interim injunction against the Independent Television Authority.

He claimed that Labour had used subliminal messages in a broadcast television [sic] on April 8. But Lord Denning, Master of the Rolls, dismissed his application. Lord Denning said the ITA was bound by law to see that broadcasts contained no subliminal matter.”

The Guardian gives more detail on the summing-up by Lord Denning:

“‘I can understand Mr McWhirter’s feelings in coming to the court for an injunction, but I don’t think this court should infer that this very important authority would disobey the statute,’ Lord Denning said.

‘It seems to me that we ought at this stage to assume that the authority is aware of the law and will abide by it by satisfying themselves that Monday’s broadcast will not include any means which infringes the law.'”

In other words: the court will take no stance on whether the broadcast on the 8th April broke the law. Nor are they going to officially order anybody to do anything. But hidden within the pleasant language is, I think, a threat to the ITA by Denning: you won’t let it happen again, will you?

The Scotsman added one extra bit of detail:

“After the hearing Mr McWhirter said he did not intend to take further action immediately. A “warning shot” had been fired which, he hoped, would be sufficient.”

And sure enough, Monday’s broadcast came and went, with very little fuss. Clearly, there was nothing at all in there which could even be remotely considered to be subliminal messaging, or else everyone would have gone through the roof, not least Ross McWhirter. The most concerned any paper gets is Harold Jackson a couple of days later in The Guardian, and even he doesn’t think there has been any issue with the actual broadcast:

“The most subliminal bit of Monday evening’s political broadcast seems to have been what was actually visible to viewers. A completely unstructured random check yesterday morning found a number of people who acknowledged seeing it, but not one who could give a coherent account of what he had seen. If Britain swings massively to Labour in tomorrow’s vote you can put it down to anything from Harold Wilson’s tobacco to Barbara Castle’s hair-do. But not to the TV broadcast.

Mr Ross McWhirter’s suspicion that Labour was beaming hidden messages through the boob tube was not sustained by the Master of the Rolls on Friday and certainly does not seem to have been sustained by anyone subjected to the overt message. If they had any sudden urges they appear to have taken the form of making coffee, getting the children to bed and, in the case of one party official, finding himself surprised not to be more bored.”

He does, however, sound a note of caution for the future, and is on the side of McWhirter’s stated point, while giving reservations about the man himself:

“Mr McWhirter’s attempted court action probably had more to do with the immediate interests of the Conservative Party than the long term interests of the nation, but that does not make it less substantial a principle. Open discussion is the essence of democracy: concealed manipulation is its destruction.”7

And that’s where this part of the story ends: fizzling into essentially nothing. Notably, ascertaining Labour’s intentions with the initial broadcast is extremely hard.8 But then that isn’t really the point of this little exercise.

Because who knew that this was all a dry run for 15 years later? Next time: the real story behind Spitting Image, Norris McWhirter, and another flash frame which ended up in court. And this time, there would be no fizzling out.

With thanks to Martin O’Gorman for the Python information, Ernest Malley for legal research, John Williams for knowing far too much about the McWhirters, and Tanya Jones for editorial advice.

Some newspapers, like the Lincolnshire Echo, report this quote as “the brain and not the eye”, which actually makes more sense. But either way round, the quote seems ill-judged. ↩

If it seems lazy of me to not really distinguish much between the two, well, they didn’t seem to do it themselves much either. When Norris wrote a book about his brother in 1977, he called it Ross: The Story of a Shared Life.

For the record, that book also contains a chapter entirely about the 1970 PPB flash frames, but for various reasons, I’m choosing to focus on the newspaper reports instead. You can borrow the book from the Internet Archive, if you’re interested. ↩

This was an ATV documentary by David Bailey simply titled Warhol. McWhirter succeeded in delaying the broadcast from its original January 1973 date, but it was eventually shown two months later. The world did not collapse. ↩

To the point of fawning. ↩

The Independent Television Authority became The Independent Broadcasting Authority in 1972, when they also became responsible for the upcoming launch of commercial radio. ↩

The Television Act 1964 merely consolidated the Television Acts of 1954 and 1963, and the following section about subliminal messaging was originally in the 1963 act. Nonetheless, it was legally the 1964 act in place at the time we’re discussing, and so it’s what I’m officially quoting here. ↩

It strikes me that many of the arguments about subliminal messaging are echoed in discussions about deepfake technology. I’ve never been worried about subliminal messaging; deepfakes concern me far more. Time will tell if I’m right, or whether I’ll end up looking as irrelevant as Harold Jackson here. ↩

My personal view is that this seems to be a case of incompetence and ignorance, rather than anything deliberate, and no subliminal messages were intended at all. But without either talking to anybody involved in making the broadcast, or having access to the relevant internal paperwork, this question simply cannot be answered for certain. ↩

8 comments

David Boothroyd on 6 August 2023 @ 10am

“Subliminal messages in advertising are ineffective, but outlawed anyway”, said the “alt.folklore.urban FAQ” on early 1990s USENET with a reference to the chapter on “Media Sources and Business Legends” in ‘The Choking Doberman’ by Jan Harold Brunvand. It basically turns out that things can’t register on the brain and and not the eye, but one thing that does register on the brain is any suggestion that it might have been manipulated unfairly, so no surprise about the deep suspicions over subliminal messages.

There was a small repeat of the 1970 Labour PPB incident in 1979 when many viewers noticed odd images during a Labour PPB transmitted on 17 April 1979 – it turned out a rushed print with chinagraph pencil editing marks had been used.

John J. Hoare on 6 August 2023 @ 11am

Yes, had I realised how in-depth these articles were going to go, I would have prefaced it with a proper piece on the history of research into the effect of flash frames. I was intending this to just be one article about The Young Ones, and it’s going to end up as four.

After I’ve finished it all, I might go back and do something separate about all that. (It’s too late to fold it into these now.) It would need a careful look at multiple pieces of research and the people behind them, so it would take a fair amount of work, but probably worth doing. Luckily, whether subliminal messaging actually works or not doesn’t really factor into these pieces, as counter-intuitive as that sounds!

Leigh Graham on 6 August 2023 @ 11am

Did anyone notice a “technical issue” in the Daily Mail piece, titled “Did Labour’s TV break the law?”, as it stated “…four of the messages were of one frame and lasted 1/25th of a second each. … ‘We understand that 1/50th of a second is the subliminal borderline.’”

Relying on my 1970’s “O” level physics lessons – and indeed the content of the quote – as TV was broadcast at 25 frames per second (in the UK) one frame of 1/25th of a second was the least time an image could be displayed, so the claimed 1/50th second borderline claimed could not have been possible. Again, from my “O” level physics, I remember that each frame is made up of two “rasters” (the CRT beam scans the screen twice for each frame, each scan is a raster) so the only possible was of achieving a flash of less than 1/25th of a second is to have a single raster contain the image, but it would only be seen on alternate lines of the frame – and I’m not sure that was even possible to achieve deliberately with the technology of the time.

John J. Hoare on 6 August 2023 @ 12pm

I nearly had a longer section about that in, but cut it for length. But my first thought when I read that Labour quote was “Bloody hell, getting a bit desperate, aren’t we?” And this is from someone who is leery about any real effect of these kind of messages, *and* someone who thinks fairly little of the McWhirters.

Not quite sure whether it was easy technically on videotaped shows in 1970, but as I understand it this PPB was delivered on film. (It’s certainly the format the BFI holds the material in.) So with film material, 1/50th would indeed be impossible.

Martin O’Gorman on 6 August 2023 @ 9pm

Fantastic article, I didn’t realise how far this went back. Interestingly, there were a couple more “subliminal messaging” jokes in Python, in shows recorded after April 1970, which I thought were just references to the old “hidden persuaders” idea that caught the imagination of the time, but after hearing about Labour’s film, I’m not so sure.

You have Gilliam’s animation in the “Bishop” episode from Series 2, where a cartoon Freemason is “de-programmed” – there are several quick flashes of an image of a naked woman next to the word “YES” printed in large red letters.

Then there’s the North Malden Icelandic Saga Society in the “Whicker’s World” show from Series 3. The quick flashes of “Invest In Malden” that eventually take over the screen entirely must be a reference to the Labour Party Political Broadcast, surely?

Incidentally, I moved to New Malden about 20 years ago. Draw your own conclusions.

Gareth Randall on 7 August 2023 @ 10pm

An image lasting 1/50th of a second – one field, in other words – would indeed have been impossible to do deliberately in an intentional way on videotape *unless* a device was specially built to generate an image for one field.

It couldn’t have been done deliberately with any editing techniques of the time (but occasionally happened unintentionally and randomly when cutting between sources on older vision mixers) and indeed it wasn’t possible with editing equipment until digital editing came along and allowed each field to be edited separately.

John J. Hoare on 8 August 2023 @ 5am

Cheers Gareth. I did think it felt unlikely, but couldn’t say for sure!

Martin: fascinating. I had completely forgotten about both those jokes, and I did a full rewatch of Python relatively recently. There’s probably a whole book to be written about all this one day, which goes into the cultural engagement with the idea.

John J. Hoare on 24 October 2023 @ 1pm

I’ve just removed a footnote from this article, as while researching Part Three, I realised it was incorrect and unhelpful. For transparency, however, I’m going to include the footnote here so you know what I deleted:

“The big question is, of course: did it break the law? I’ll give my opinion, but hide it in a footnote like a coward. The key part of the Television Act here is the line forbidding “images of a very brief duration”. Labour admitted that “four of the messages were of one frame and lasted 1/25th of a second each”. To me, this very clearly counts as images of a very brief duration. The wrinkle comes with Labour’s contention that there were also “Labour Tomorrow” messages which were “one of four frames and one of eight frames”. If the same message is visible on longer flashes, do the others count as subliminal messages under the terms of the act?

My gut feeling is that yes, they do, and the 8th April broadcast was infringing. But it’s not exactly a clear cut case, and in retrospect the Court of Appeal neatly dodging having to rule on that point feels fairly understandable.”

Comments on this post are now closed.