Breakfast, 25th December 2024.

“You’ll be regional again before you know it…”

Breakfast, 25th December 2024.

“You’ll be regional again before you know it…”

Where were you when Napalm Death appeared on Children’s BBC?

For me, the answer was… not watching Napalm Death on Children’s BBC. Music show What’s That Noise? was not a favourite of mine. Perhaps I detected the vague whiff of education, and I’d already had enough of that by that point in the afternoon. At 4:35pm on the 10th October 1989 I was probably watching Sooty and Count Duckula on the other side. Or on my computer. Or eating tea. Anything, in fact, than watching BBC1.

Oh well, my loss. See how great Craig Charles is here. “This is music for young lovers, step aside Kylie Minogue!”

The question is: what has the above moment got to do with Red Dwarf, beyond the involvement of Craig?

Due to complicated work stuff, it may be a bit of time before the next significant article here on Dirty Feed. So now seems a excellent chance to point you towards Jonathan Bufton‘s series of articles on 90s Saturday morning kids show Parallel 9. These started way back in 2022, and the final piece went up in April, which seems an good excuse to read them all over again.

I’ve linked to some of these pieces before, both on the main site and my newsletter, but the reason they deserve so much love is because really are gold-standard stuff on how to write about the TV programmes of your youth: interviews, paperwork, and examining the actual material properly. So many people are content with a sneer, or half-remembered nonsense, and in unfortunate cases both. Jonathan does things properly.1

I found Part 5 particularly interesting; it’s about Series 3 of the show, long after I’d drifted away from the series. (I remember precisely nothing about The Little Green Man, by all accounts one of the most popular features the show ever had.) But if you’ve not read any of the above before, set aside a couple of hours, and throw yourself into some of the best pop culture writing you’ll ever find.

And as I always say – if you want writing like that online about your favourite forgotten show, and it’s conspicuous by its absence… there’s only one way to solve that one. Get scribbling. The thing I’ve learnt most from writing Dirty Feed is that it’s easier than many think to find a unique take on something. It hasn’t all already been written.

In fact, sometimes virtually nothing has been written.

Disclaimer: I did give Jonathan some minor help on these pieces, but that’s not why they’re amazing. ↩

Sometimes my knowledge of a popular science fiction sitcom can reach mildly irritating proportions. When this happens, I do feel the urge to share it with you, and spread the irritation around equally,

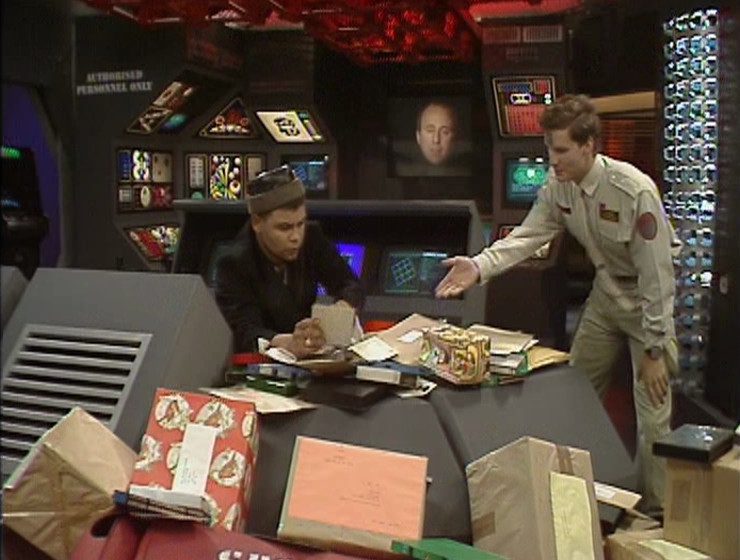

Take the following episode of Press Gang Series 4, “Love and War”, broadcast on the 28th January 1992. We are particularly interested in the voice of Colin’s ludicrous electronic briefcase.

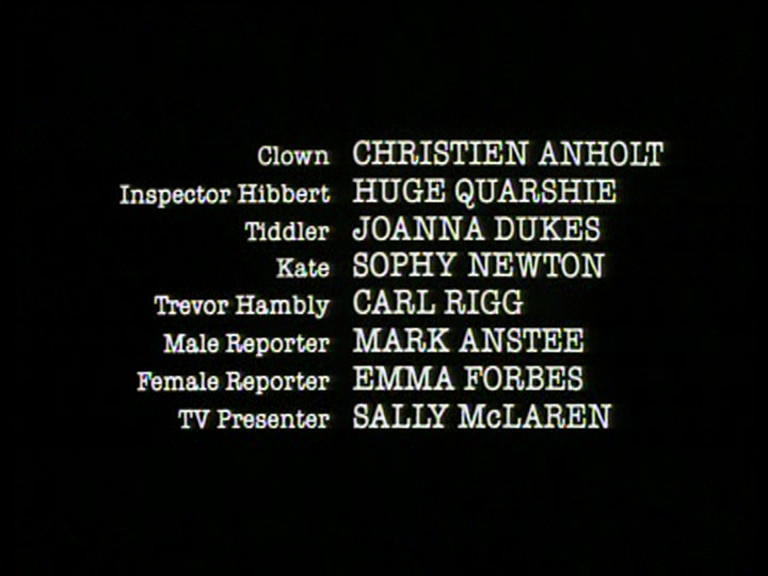

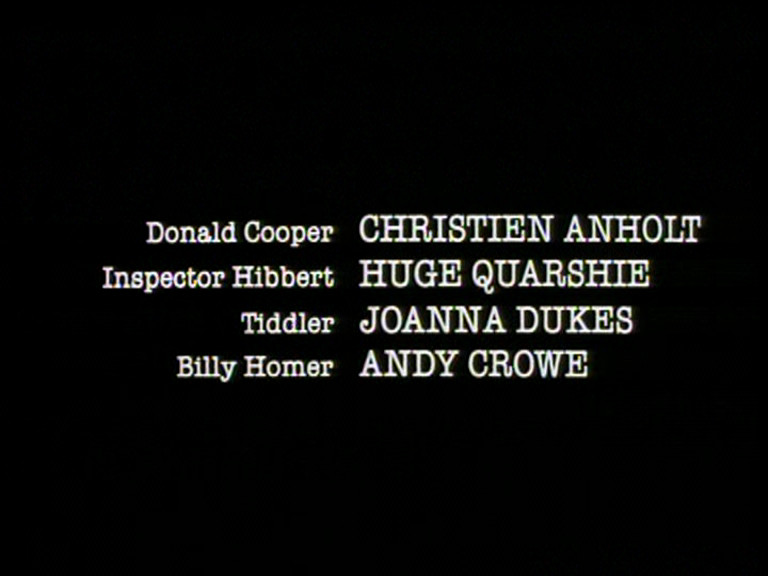

Now, the actor for the briefcase isn’t listed in the end credits. Which is peculiar – sure, it’s only a voice, and an electronically altered one at that, but it’s very clearly a comedy performance. But not to worry. Because I recognised that voice.

Here’s a clip from Red Dwarf, “Emohawk: Polymorph II”, broadcast nearly two years later, on the 28th October 1993. The gang are being tracked by a Space Corps External Enforcement Vehicle, whose voice should sound rather familiar:

Luckily, the voice is actually credited in Red Dwarf. It’s Hugh Quarshie, probably best known as Ric Griffin for nearly two decades of Holby City, as well as appearing in The Phantom Menace, and a million and one other things.

And one of those million and one other things? Erm, Press Gang. Specifically, the two parter “The Last Word” in Series 3, broadcast on the 28th May/4th June 1991. With that, the final piece of the puzzle clicks into place: Series 3 and 4 of Press Gang were produced and shot simultaneously.

So who did Quarshie play in “The Last Word”? Answer: Inspector Hibbert, an important character with a crucial moral choice at the end of the show. I won’t spoil that moral choice if you haven’t seen it, but here he is from earlier in the story:

Those two episodes are some of the most serious material the show ever did. Who knew that Quarshie’s turn as an Inspector in a two-parter mediating on gun crime, suicide, and the nature of guilt would be followed up with… a silly talking briefcase? Come to think of it, that seems to be Press Gang in a nutshell.

Still, it really is a shame he wasn’t credited in “Love and War”, but at least Hugh Quarshie got a proper credit in “The Last Word”.

Huge Quarshie?

Oh well.

With thanks to Christopher Wickham. A version of this post was first published in the November issue of my monthly newsletter.

This is the kind of thing I randomly find on my hard drive. Enjoy.

Hacker Time, Series 5 Episode 10, 7th August 2015.

Here’s a timely question. What’s the connection between William Friedkin, and Knightmare?

The answer isn’t to be found in anything which was actually broadcast. Because Knightmare had two unbroadcast pilots. One called Dungeon Doom, a 15-minute proof-of-concept recorded in early 1986, and the other, actually called Knightmare, which was a full episode recorded in January 1987.1

And the title music for that second pilot was “Betrayal” by Tangerine Dream: the main theme to Sorcerer, directed by Friedkin in 1977:

The music was also used in the trailer for the film:

It has to be said, what an absolutely wonderful choice of music that was for the Knightmare pilot. I wouldn’t trade Ed Welch’s incredible theme for anything, of course, but “Betrayal” perfectly captures the mood of the series: dark, foreboding, electronic. It could easily have been used as incidental music in the show proper.

But how do we know that second pilot used “Betrayal” for its main theme? Sadly, despite people’s hopes over the years, neither pilot has ever actually leaked online. Which is something that has become increasingly bizarre. The show has a still-active fandom over at Knightmare.com, and next January that site will have been going for 25 years. It’s something which feels like it should have made it out there by now… but hasn’t. Maybe one day. Preferably before I snuff it.

We do, however, have the next best thing. Back in 2010, Billy Hicks got hold of the script of that second pilot, wrote about it, and uploaded the full thing. And as part of that script, we’re told:

Title Music – Tangerine Dream ‘Betrayal’/E Froese, C Frauhe, P Bannman/MCA Records Inc/MCL 1646/Sd2/NV2

The script itself is fascinating, and not just because you can spot the differences between the pilot and Series 1. It’s close enough to the first broadcast episode of Knightmare that it really gives an insight into how the show was put together in those early years. The multiple responses needed by actors must have been absolute agony to learn.

So when you get a moment, give that script a read, and try listening to “Betrayal” in the background. It’s almost as good as actually watching that unbroadcast pilot for real.

Almost.

See Tim Child’s How Knightmare Began for the full story. ↩

As pointed out to me on Twitter, the script manages to misspell both Christopher Franke and Peter Baumann’s last names. ↩

Sometimes, if I put on my magenta-tinted spectacles, I think that the most fun I ever had with Red Dwarf was in 1994. That was the very first time I watched the series, and indeed the very first time the show had been repeated from the beginning at all. So I could blithely enjoy the show without being troubled by what other people thought of it… or specifically, what the writers thought of it.

So the fact that Rob Grant and Doug Naylor hated the grey sets by production designer Paul Montague in the first two series of Dwarf was unknown to me. I really liked them. I also liked the new sets from Series III onwards, by Mel Bibby. I just… liked Red Dwarf an awful lot. And Grant Naylor poking fun at the sets of their own show in Me2 (TX: 21/3/88) entirely passed me by.

LISTER: But why are they painting the corridor the same colour it was before?

RIMMER: They’re changing it from Ocean Grey to Military Grey. Something that should’ve been done a long time ago.

LISTER: Looks exactly the same to me.

RIMMER: No. No, no, no. That’s the new Military Grey bit there, and that’s the dowdy, old, nasty Ocean Grey bit there. (beat) Or is it the other way around?

Truth be told, I still love those early Red Dwarf sets, and no amount of people who actually worked on the show slagging them off will change that. In particular, I think the endless permutations of the same basic sections did a really good job at selling the ship as something genuinely huge, and I don’t think this is acknowledged enough. I didn’t even mind the swing bin.

Ah, yes, the famous swing bin. Of all the elements made fun of with those first two series, this one is a perennial. You can see it in action during the very first episode, “The End” (TX: 15/2/88), in McIntyre’s funeral:

It is undeniable: McIntyre’s remains are blasted into space through the medium of a kitchen swing bin, built into a circular table-like object. The commentary on this scene in the 2007 DVD release The Bodysnatcher Collection is brutal:

DOUG NAYLOR: The idea of this is was that it’s supposed to be quite moving, wasn’t it?

ROB GRANT: Yeah, I liked this scene in the script, because it was tender, and a different tone.

DOUG NAYLOR: Yes, but obviously it’s not working as conceived? Now first of all…

ROB GRANT: The canister.

DOUG NAYLOR: The canister, and then the… kitchen bin.

ROB GRANT: Just fantastic! But he pressed that button good, that’s good button-pressing acting… I mean, what is that? It’s not even a good bin, is it?

DOUG NAYLOR: And because there’s nothing in the bottom of the kitchen bin, it just thuds to the bottom, and I think eventually they put tissues in so it didn’t make that terrible clanking noise.

ROB GRANT: Oh dear Lord.

The above scene did actually go out as part of the first episode. But our notorious swing bin also played a big part in what has become one of the most famous deleted scenes in the whole history of Red Dwarf. Shot during the original recording of the first episode, but cut from transmission, we see Lister trying to give a respectful send-off to the crew.

Rimmer’s “What a guy. What a sportsman” is one of the great lost lines of Red Dwarf, as far as I’m concerned. Swing bin or no.

So, what happened to our notorious prop, after the first episode was completed? Well, it hung around in the Drive Room set for the rest of the series, sometimes used as a table whenever the need arose:

Waiting for God

Confidence & Paranoia

But once those first six episodes were over, that was it. Series 1 was recorded at the tail end of 1987; when Series 2 started recording in May 1988, not only was our famous swing bin prop nowhere to be seen, but the entire Drive Room set had been replaced, with something rather less… grey.

Series 1 Drive Room

Series 2 Drive Room

Surely our swing bin was never to be seen again?

Here is today’s bold and dangerous statement here on Dirty Feed: Danger Mouse did not get viewing figures of 21 million viewers in 1983.

To me, this statement would seem to be self-evident. The idea that Danger Mouse beat every single episode of Coronation Street broadcast that year would seem to be highly dubious. Many others, however, seem to disagree. Take this BBC News article from 2013, “How Danger Mouse became king of the TV ratings”:

“A curiously British cartoon, it parodied James Bond and was influenced by Monty Python’s anarchic humour.

Thirty years ago children’s cartoon Danger Mouse topped the TV ratings, beating even Coronation Street. But what happened to the legendary Manchester animation house Cosgrove Hall Films, which created the rodent secret agent?

Voiced by Only Fools And Horses star David Jason, Danger Mouse was the flagship of Cosgrove Hall Films, based in a quirky studio in the Manchester suburb of Chorlton-cum-Hardy.

Vibrant, surreal and deliciously silly, an astonishing 21 million viewers reportedly tuned in to watch it in 1983, a record for a children’s programme which has yet to be beaten.”

But the BBC are far from alone in reporting this. A quick Google search reveals this factoid to be absolutely everywhere. Sure enough, many people clearly grabbed it from the 2013 BBC News piece, as in this extremely recent piece in the Manchester Evening News, “Calls for a Danger Mouse statue in Chorlton”:

“A resident has called for a Danger Mouse statue to be erected in the centre of Chorlton.

A post by Andrew Jones in the Facebook group Chorlton M21 shared the idea of crowdfunding for a Bronze statue of the animated mouse on the corner of Barlow Moor Road and Wilbraham Road.

The idea proved popular and was met with more than 150 likes.

Silly, exciting and with a huge amount of custard, Danger Mouse was a huge success on screen, and in 1983, once racked up 21 million viewers, beating Corrie, and smashing records for the highest viewings of a children’s show.”

Other sources are rather more troubling. When I first started researching this article, I thought the 21 million figure might just be traced back to an over-enthusiastic fan, and we could just have a jolly good laugh at their expense. Unfortunately, this is very much not the case. In 2020, The Guardian posted “How we made Danger Mouse – by David Jason and Brian Cosgrove”.

And what does Brian Cosgrove, co-creator of Danger Mouse have to say?

“I worked with a small group of animators. We had certain rules. Danger Mouse was a mouse living in a world of humans. When he drives around London, his car is mouse-sized – he could get stepped on! That’s what I like about animation: you can ignore common sense. We never talked down to our audience. Children were mature people, just small. We didn’t realise were making something that would achieve such a level of affection. It certainly wasn’t due to the quality of the animation, but I think Danger Mouse had heart. At one point in the early 80s our viewing figures – 21 million – were higher than Coronation Street’s.”

Ah. Erm. Hmmmm. OK.

When the co-creator of the show is literally stating the 21 million viewing figure as fact, the onus is on me to prove that the figure is false, rather than pointing and saying “don’t be ridiculous”. And sure, we can easily have a first stab at that. If we look at the Top 10 rated programmes in 1983 from BARB, we can see that the highest rated programme that year was Coronation Street… with viewing figures of 18.45 million. And 18.45 million is a figure which is lower than 21 million, I am fairly confident in stating.

But I think we need to go deeper. Where exactly does this 21 million figure come from?

* * *

I’m not sure I can answer that for sure. But I can pinpoint a relatively early reference to it. Much earlier than 2013, at least.

From the BBC itself, we have this image gallery published in 2006, which confidently states:

“Danger Mouse (1981 – 1992): The world’s greatest Mouse detective Danger Mouse with his trusty sidekick Penfold achieved cult status and in 1983 viewing figures topped 21 million!”

But we can go further back, and to a rather more primary source to boot. The old Cosgrove Hall website – now long gone, but preserved on the Wayback Machine – has this to say about Danger Mouse, published right back in 2002:

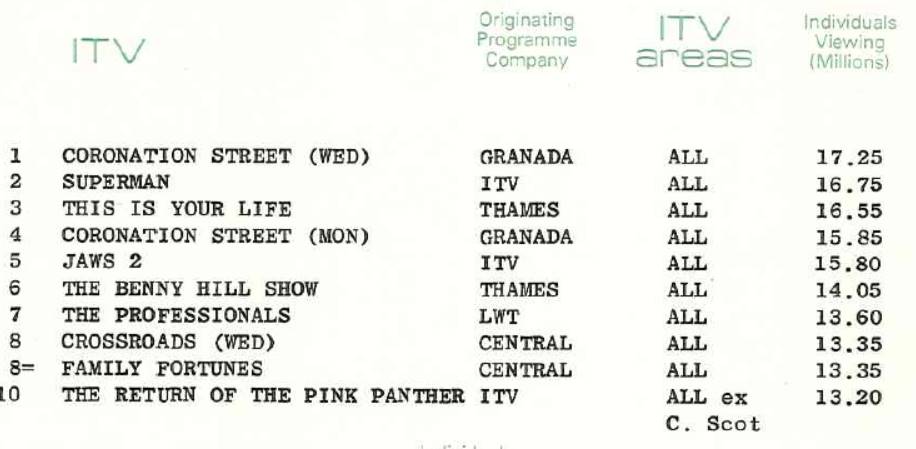

“At one stage in early 1983 Dangermouse viewing figures hit an all time high of 21.59 million viewers. In the same week the movie Superman managed a mere 16.76 million!”

Which suddenly gives us some extra information to work with. We have a very specific figure of 21.59 million, and – crucially – we now know that Superman was broadcast in the same week as the supposedly record-breaking Danger Mouse figures.

Superman – its UK television premiere, no less – was broadcast across ITV on the 6th January 1983. And Danger Mouse was also on that week: in fact, it was the opening episodes of Series 4.1 Between the 3rd – 7th January 1983, the five part serial “The Wild, Wild, Goose Chase” were broadcast. And all of a sudden, we’re not waving vaguely at “21 million viewers in 1983” – we have a very specific week we can investigate.

Reader, I have investigated. I have gone beyond the annual figures on the BARB website, and asked them for anything they could provide for this specific week. Incredibly, they actually indulged me. Here is the Top 10 programmes for ITV, for the week ending 9th January 1983 – figures not publicly available anywhere else online, as far as I am aware:

Danger Mouse is nowhere on that list. Moreover, the top-rated programme of the week – Coronation Street – had viewing figures of 17.25 million, significantly below 21.59 million. As far as I am concerned, case closed. Danger Mouse wasn’t pulling in viewing figures of 21 million viewers. It wasn’t even close.

As to why Cosgrove Hall were claiming that figure… I can’t say. 21.59 million is an extremely specific number. Moreover, Cosgrove Hall’s claim of Superman getting 16.76 million is pretty much correct.2 It is rather tempting to suggest that somebody with a dodgy grasp of mathematics added up all the figures throughout the five episodes shown that week, and that each episode got a rather more reasonable 4.3 million instead. Sadly, BARB seem to have no record of Danger Mouse figures at all from 1983, so there’s no way of proving or disproving that theory.

Other potential solutions are available. Maybe the 21 million includes overseas viewing figures. Or, y’know, maybe the decimal point is just in the wrong place. Who knows? All I know is that Danger Mouse very much did not beat Superman, at least on its own terms.

I will, then, leave you with one final thought. Recently I received copies of the 1984 and 1985 Danger Mouse annuals. If the show had been getting 21 million viewers back in 1983, you would think there would have been at least some mention somewhere in those annuals. Frankly, you’d expect it plastered across the front cover.

There is nothing.

Danger Mouse didn’t get viewing figures of 21 million. Tell your friends.

UPDATE (9/11/21): The great thing about writing this site is that I can put together an article, fail to quite reach the end of the story, and then have a reader step in and do the final part for me.

So many thanks to Anthony Forth, who has done some further research on all this, and actually managed to prove what we all suspected. Consulting the full BARB Weekly Report for the week ending 9th January 1983 – available at the BFI library – the viewing figures for the Danger Mouse episodes in question are as follows:

Those figures add up to 20.875 million. Which doesn’t quite match the 21.59 million that Cosgrove Hall quoted, but is very much near enough to conclusively prove where the erroneous 21 million figure came from. And let’s be very clear about this: it is erroneous. You don’t get to add together your five different episodes across the week, and say you beat a single showing of anything else. That’s not how viewing figures work.

Anthony also points out that the Bank Holiday Monday figure of over 7 million is very high for the series – twice that of what the BBC was getting at the same time, and more than the programmes which followed on ITV. His theory that this success got conflated and exaggerated over time into “beating Superman” seems to me to be a very sound one.

It’s also worth noting that the figures for the following week’s serial, “The Return of Count Duckula”, are as follows:

The total for this serial comes to 21.628 million… or more total viewers across the week than the supposedly famous serial in the same week as Superman. And with that, I think we can safely put this nonsense to bed.

After all: over 7 million viewers for the first episode of the serial is still pretty damn good for the slot. We don’t need to misrepresent anything for that to be considered a success. Danger Mouse did well enough without all that.

There are many pieces of terrible pop culture writing online. I’ve done plenty of it myself. But sometimes, a piece of work is so dreadful, that it lingers in your head for well over a decade. To the point where it actually falls offline, and you need to use the Wayback Machine to find it.

Such was the case with this piece on Knightmare from 2002. And it really is absolutely bloody awful.

The scene is set in the third paragraph, with possibly the least promising sentence ever written:

“Actually, as I write, I realise that I haven’t seen Knightmare for sodding years.”

An admission which leads to beautiful moments like this:

“It got rubbisher, as well: in a desperate attempt to fiddle with the formula, the producers ditched many of the more atmospheric locations and charismatic characters (notably Pickle, Treguard’s wonderful gay elf sidekick) in favour of comic hangers-on and tedious gimmicry. The eyeshield, anyone? Pah.”

Unfortunately, the facts are as follows: both the eyeshield and Pickle debuted in the same series. Series 4, to be exact.1

After that, deconstructing the article is like shooting fish in a barrel, to the point where it’s pretty much worthless. For instance, take this, on why Knightmare ended:

“It died because its niche fanbase eventually either a) got older, b) got computers or c) got sex – in any case, the market for its pedestrian, camp fantobabble was never going to last.”

This article was published in 2002. Three years earlier, creator Tim Child had already written a history of the show on Knightmare.com, which gave detailed reasons for why the show wasn’t recommissioned. But the writer of this piece isn’t interested in the actual facts; they’re interested in a pithy turn of phrase. Which also explains the bizarre line about “pedestrian, camp fantobabble”, which comes out of absolutely nowhere.

I could go on – what the hell is the bit about the “niche fanbase” all about, when it was an absurdly popular show, and a touchstone for a generation? – but you get the point. The main reason I bring all this up is because I realised the other day exactly how much this article influenced me when it came to writing my own piece about Knightmare, published last month. A piece that yes, has its fair share of reminiscing about the show.

It also throws in plenty of cold hard facts, as well. It transcribes actual sections from the show. It quotes Tim Child twice, from two separate sources. It’s a piece which proves you can still write about your memories, and fact check them at the same time without destroying anything.

That old piece from 2002 makes a point of acknowledging “nostalgia’s rose-tinted eye”, but doesn’t actually do anything about it. The way to avoid nostalgia is to watch and research what you’re writing about. And who knows? You might find that what you’re writing about doesn’t “look a bit, erm, crap”. You might just find it’s still fucking great. And if you don’t think it’s great, at least you can explain why, rather than guessing.

And I write this not because I want to say I’m brilliant. Well, not entirely. But it did shape something in my approach to writing that I think is worth noting: that just because you’re writing about pop culture, it doesn’t absolve you from doing the legwork. Just because you liked a kid’s TV show when you were younger, it doesn’t mean your half-remembered guff about it is enough.

Realising that at least sets you on the right path, however well you ultimately manage to traverse it. I think I get to the start of Level 2 before being killed off, but at least that’s better than dying in the first room.

There’s also no evidence that Pickle was gay, either, but I have no issue with slash being written about him. ↩

It’s 1990, or something vaguely close to it. I’ve cleaned my teeth like a good boy, and am now running to my room. Something is going to get me, you see. I mean, I have a happy home life. So happy that my parents even make sure I clean my teeth. But right now, I’m in danger.

I barge into my bedroom, flinging the door open, and dive under the covers. I lie, panting. I strain my ears, but of course, everything is fine. As long as I’m under the covers, I’m safe.

But I’d best not come out. I can see it in my head. A decomposing skull. It followed me into the room, and is now sitting against my bedroom wall. If I come out, it’ll zoom into my face and kill me.

It’s hot under the duvet. Far, far too hot. It’s the height of summer. Sweat covers my body. I do an experimental waft of the duvet to cool me down. It’s frightening enough – it gives the manifestation on my wall a moment of opportunity – but I get away with it. I drift into a fitful sleep. I might even dream about that… thing.

It’s just waiting for me, you know.