For more on this BBC100 series of posts, read this introduction.

“Tonight is Halloween when strange things can happen, and even here live on BBC1, all is not what it seems.”

And with those foreboding words on Halloween night 1987, the BBC1 globe transformed into a pumpkin, and one of the most remarkable pieces of television ever transmitted began. Because this was the night that Paul Daniels was killed, live before the nation. Nobody who saw it would ever forget it.

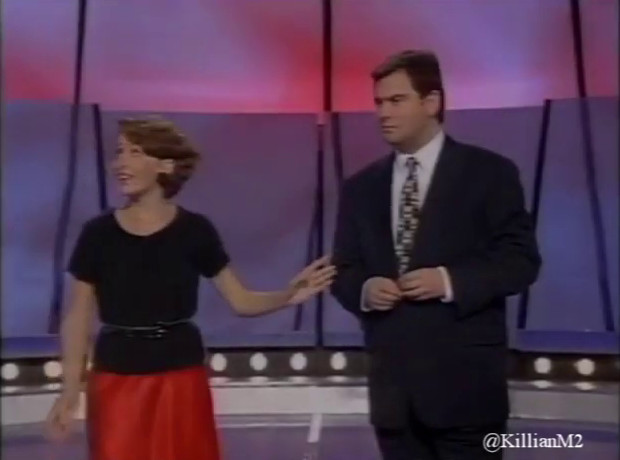

Oh, the show starts simply enough, if atypically. The Paul Daniels Magic Show had been running since 1979 on the BBC. But instead of the usual bright, light entertainment studio, we’re greeted with a horse and carriage moving through the smoky blackness. Paul Daniels and Debbie McGee exit the carriage, in what only can be described as gothic evening dress. And after a mild levitation trick outside the main entrance, they enter a grand mansion, where we will be spending the next 40 minutes.

Yet once the show gets going, most of the programme isn’t that much different to a normal episode of Paul Daniels. Paul tells us a story about a Houdini seance, which is an excuse for some messing around with props. Eugene Berger makes two lovely appearances and does some close-up magic. Perhaps the most intriguing section is an extended setup involving a battery powered video camera, television, a representative from Panasonic… and, of course, a ghost. But even this isn’t really outside the bounds of the kind of thing his show usually does; three years earlier, he’d done a “disappearing camera trick” which is really in the same, erm, spirit.

But this is all a lead-up to the final six or so minutes. After some short film of a Houdini escape, Daniels is revealed standing in front of a huge iron maiden, the famous medieval torture device. This is to be an escape trick. “The spikes themselves – there’s 110 of them – and they’re all metal”, Daniels says, matter-of-factly. As he gets get securely fixed into the contraption, he asks Debbie to leave the room entirely. “We have people here from all walks of life. If anything at all goes wrong, don’t move from your seats unless instructed to do so.” A screen is placed in front of the iron maiden, and the escape attempt starts.

Unfortunately, something goes hideously wrong. After a few seconds, the absurdly heavy door slams shut. There is a nasty pause, and no sign of Daniels. The picture fades to black. “Ladies and gentlemen”, an unknown voice intones, “Please leave the room in an orderly fashion.” And the end credits roll, to silence. Paul didn’t complete his escape, and is now rather intimate with those solid, 110 spikes he was boasting about just a few moments ago.

Except, of course, he wasn’t. The lack of escape was the trick; a macabre piece of black theatre, perfect for Halloween. It was, however, not a piece of theatre that some viewers appreciated. Indeed, outrage was so strong that Paul ended up sending in a letter to The Times explaining himself. It’s a brilliant piece of writing, and one which not only talks about the specifics of his Halloween show, but also talks in philosophical terms about the problems faced by all television across the decades:

“In television we are, for the most part, in a no-win situation. If we continue to turn out the same format, week in week out, we are heavily criticised along the lines of “same old faces, same old scripts”, “very boring” etc, and yet when someone decides to change the format and step outside the “norm” the criticisms still come.”

As for the show itself, he provides a robust defence:

“Please remember the following facts. You were warned in the final announcement before the show started that all is not as it seems. You received definite instructions to switch off before the final trick happened if you were of a nervous disposition (If you ignored that warning that is your fault not mine). Didn’t you think it amazing that within two or three seconds of the trick ending, the BBC had on standby all the credits on a black background instead of our normal credit sequence…?”

Indeed the thing that strikes me most about the programme is how utterly fair it is on the audience. The continuity announcement all but tells you what is due to happen, if you interpret it correctly. Daniels does indeed warn you before the final trick takes place. (“I have to warn you – this can go wrong. That is not a joke. Switch off if you are of a nervous disposition…”) This is not a programme which pulls a nasty stunt with no warning. It gives you all the information you need, and then does things so perfectly that it still ends up as a shocking piece of television.

Then there’s the final moment, after those silent end credits roll. Paul Daniels himself pops back up, and does a short piece to camera. But it’s no naff “Here I am, don’t worry, I’m fine!” moment. (At least, not yet – the production did have to do one of those to be transmitted after the subsequent programme of the evening, which is a bit of a shame.) Instead, it’s altogether more subtle:

“Well, what you have just been watching was a live magic show. But this, outside here, was recorded yesterday, and all I can say is: I hope that the last illusion goes well tomorrow…”

And Daniels winks to camera. And not only is it a great joke, but it’s the utmost in treating the audience with respect. It relies on people understanding the difference between the live parts of a programme, and pre-recorded inserts in the same show. Clearly, some people didn’t get it. But I’ll choose programmes which overestimate their audience to ones which underestimate them, and maybe we could do with a bit more of the former today.

The show started something of a trend for the BBC to mess with its audience during Halloween. Five years later, the infamous Ghostwatch aired; a drama presented as a live broadcast which slowly becomes haunted itself, ending in a national mass seance. And in 2018, Inside No. 9 produced “Dead Line”, a hoax which many had thought the BBC was incapable of still doing. What other show has not only featured a fake channel breakdown, but our friendly continuity announcer being killed live on air?

But Paul Daniels was first. And for my money, best. He could have settled for doing a spooky version of his normal show, with a few pumpkins dotted around. It still would have been great fun: even his standard shows were superb TV. Instead, he pushed the boundaries of television as far as they could possibly go. All under the innocuous guise of light entertainment.

Read more about...

bbc100