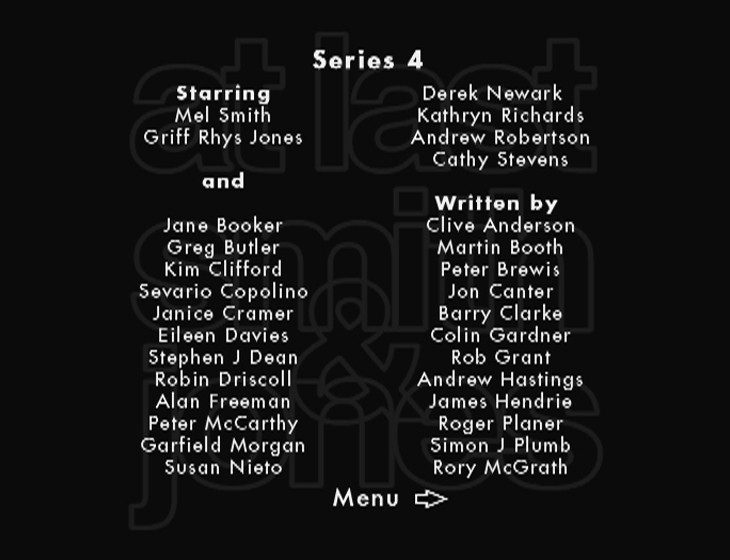

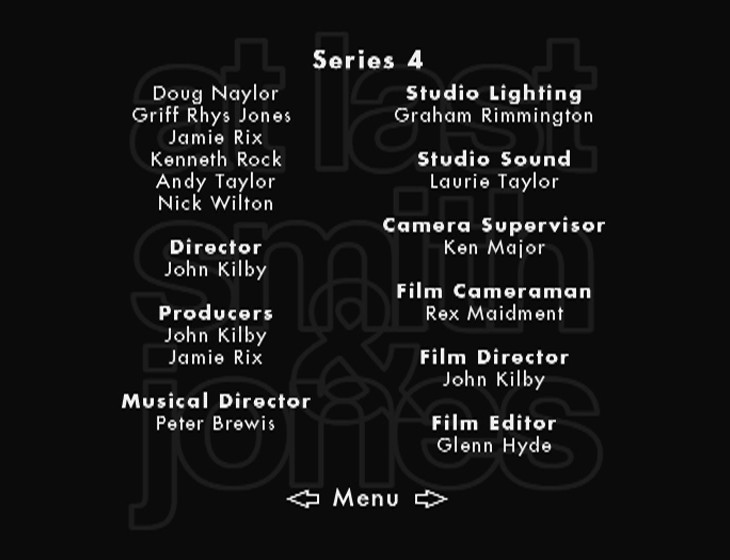

There is something very suspicious about Series 4 of Drop the Dead Donkey, you know. And it involves poor old downtrodden news editor George Dent.

For years, we’ve heard about his dreadful life with Margaret, his wife. About her cruelty towards him, about her affairs, about him having to go and sleep alone in the attic… and about how she eventually divorces him. This comes to a head early in the aforementioned Series 4, with “The Day of the Mum” (TX: 13/10/94). The day Margaret remarries.

Except brilliantly, rather than resulting in more misery for George, the episode culminates with his delicious revenge instead:

DAVE: Oh no, let me get this straight. You hired a beautiful call girl to accompany you to your ex-wife’s wedding just to rub her nose in it, and then you got this woman to make a pass at the groom… and ruined their wedding day. That’s what you did, isn’t it George?

GEORGE: Yes. That’s what I did. And it was the best £2000 I have ever spent.

Indeed, for a while, things begin to look up for George. In “Helen’s Parents” two weeks later, he’s met someone new. And not some “sad old spinster who’s picked up George because her favourite Labrador’s died”, as Henry so delicately puts it. She’s gorgeous.

GEORGE: I’d like you all to meet Anna, everybody.

ANNA: I am very pleased to meet you all.

GEORGE: Anna is from Poland.

ANNA: But now my English is quite good. One day I hope to even understand Loyd Grossman.

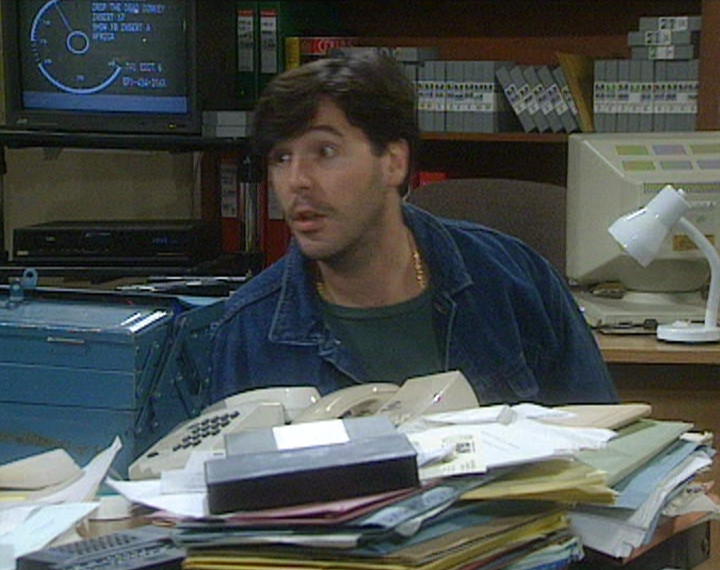

In case you thought the show would let George be happy for long, you are very much mistaken.1 The very first time we see her alone with George in his office – “This is my wall planner – where I plan things… on my wall” – we are immediately suspicious of Anna’s reactions. The show doesn’t leave us with much mystery about her intentions towards him.

Unlike in real life, where Jeff Rawle ended up marrying Nina Marc, who plays Anna, in 1998. And they’re still together. Awwwww. ↩