Part One • Part Two • Part Three • Part Four • Part Five

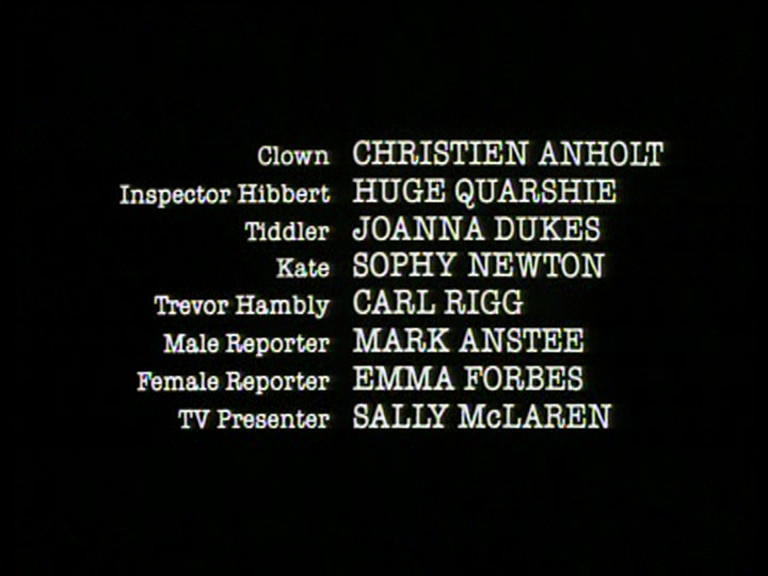

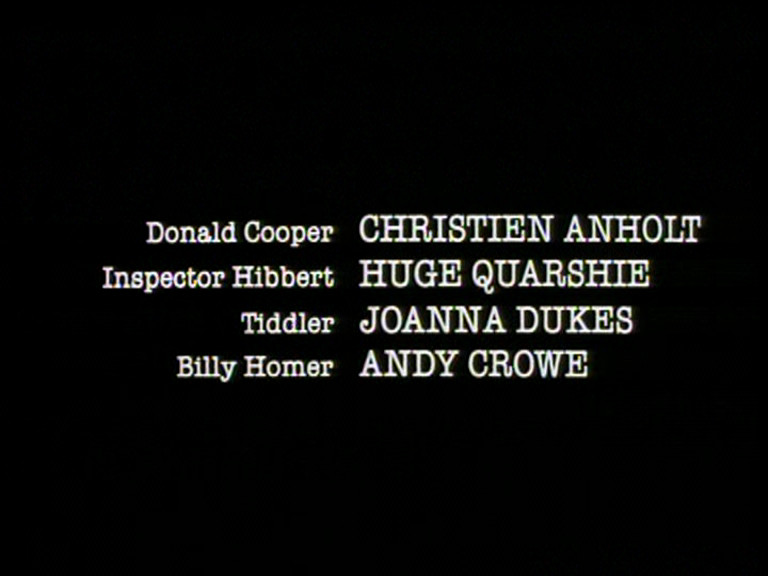

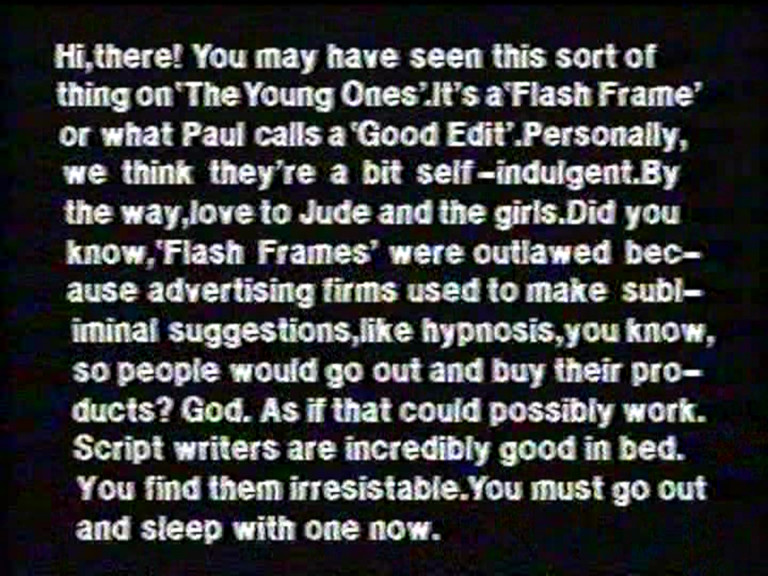

It feels like ages since we last checked in with The Young Ones. A brief recap, then. Back in 1984, the BBC had just transmitted the show’s second and final series… but not without some problems. In particular, the final flash frame intended for inclusion in “Summer Holiday” was cut entirely, much to the displeasure of the team. But surely the show was now home and dry?

Well, what do you think?

A hint of what was to come can be found in the following from Hansard. It isn’t normal for questions to be asked of Ministers about a sitcom.1 And yet on the 27th June 1984, just eight days after Series 2 of The Young Ones had finished airing, that is exactly what happened. Conservative MP for Cardiff West, Stefan Terlezki, was our ersatz Norris McWhirter.

“Mr. Terlezki asked the Secretary of State for the Home Department what safeguards there are against subliminal messages appearing on the British Broadcasting Corporation; and if he is satisfied that these are adequate.”

Douglas Hurd, then a Minister of State for the Home Office, gave the following reply:

“I am satisfied that clause 13(6) of the BBC’s Licence and Agreement of 2 April 1981, which requires the corporation not to include subliminal messages in its programmes, provides an adequate safeguard. It is for the BBC’s board of governors to ensure that the provision is observed. I understand that the corporation considers that some brief, unrelated inserts included in a recent BBC comedy series might have been regarded as in breach of the spirit of the provision, and steps were taken to prevent a recurrence.”

Which brings up an interesting question: were subliminal images really banned on the BBC at the time? The above suggests that they were. And yet Paul Jackson, on the 2007 DVD documentary The Making of The Young Ones, seemed to disagree:

“And although it wasn’t illegal at the BBC because the commercial issue didn’t arise, it was raised, and it went up to Bill Cotton… and the edict came down you’ve gotta take it out.

Meanwhile, the Nottingham Evening Post, on the 16th June 1984, reported the following:

“A BBC spokeswoman said the BBC’s Charter does cover subliminal techniques, from the political and advertising point of view, but that these pictures could not be deemed harmful.

“This is a joke flash-frame technique which is harmless”, she said.”

There’s only one way to find out the truth. We need to get hold of a copy of the BBC’s Licence and Agreement. Not this damn thing, dated December 2016, but the document quoted by Hurd from April 1981.

I have a copy. Clause 13(6) states the following:

“The Corporation shall at all times refrain from sending any broadcast matter which includes any technical device which, by using images of very brief duration or by any other means, exploits the possibility of conveying a message to, or otherwise influencing the minds of, members of an audience without their being aware, or fully aware, of what has been done.”

Which sounds suspiciously familiar. Let’s compare this to Section 4(3) of the Broadcasting Act 1981, which IBA-licensed stations were supposed to abide by:

“It shall be the duty of the Authority to satisfy themselves that the programmes broadcast by the Authority do not include, whether in an advertisement or otherwise, any technical device which, by using images of very brief duration or by any other means, exploits the possibility of conveying a message to, or otherwise influencing the minds of, members of an audience without their being aware, or fully aware, of what has been done.”

The similarity in language is obvious. At the very least, the intent for the BBC was exactly the same as for the IBA: to strongly discourage the use of flash frames. Whether it would have stood up in a court of law is a different question, and one which was never answered in practice.

[Read more →]

Read more about...

freeze-frame gonna drive you insane, the young ones