This is the kind of thing I randomly find on my hard drive. Enjoy.

Hacker Time, Series 5 Episode 10, 7th August 2015.

This is the kind of thing I randomly find on my hard drive. Enjoy.

Hacker Time, Series 5 Episode 10, 7th August 2015.

On the 9th March 1981, BBC2 first broadcast the Yes Minister episode “The Death List”. It’s a particularly good episode for many reasons, not least Graeme Garden marching into the programme for one show-stealing scene, and turning it into The Goodies.

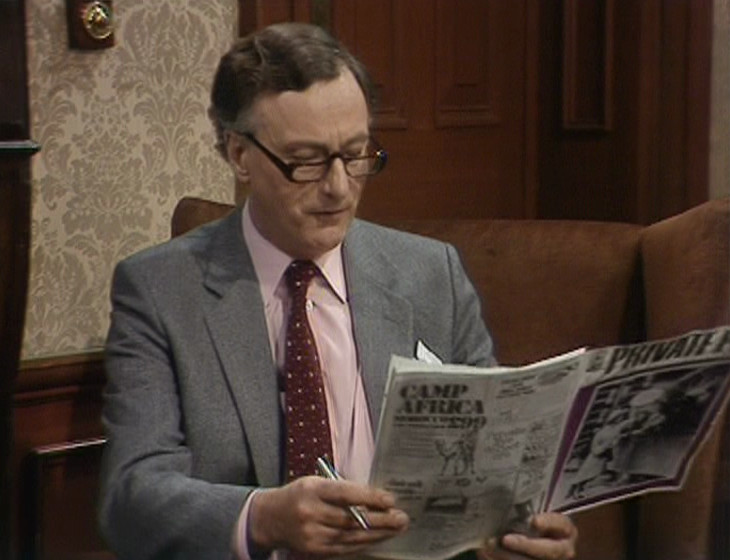

But that’s comedy, and we don’t deal with comedy around here. We deal with far more important things. Such as: which issue of Private Eye is Jim Hacker reading from here?

Is it a real issue of the magazine? Or is it a prop, made from scratch?

Let’s see what we can dig up. Our first point of call is, of course, Private Eye‘s covers library, which usefully gives us an image of every single cover since the magazine’s first issue. And to help narrow down the search, we also know that “The Death List” was recorded in studio on the 1st February 1981. Did they just grab the latest issue of the Eye and bung it in Paul Eddington’s hands?

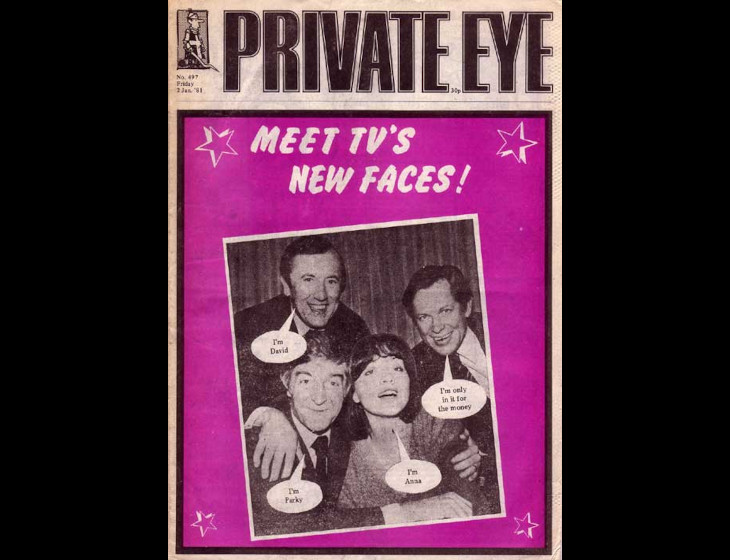

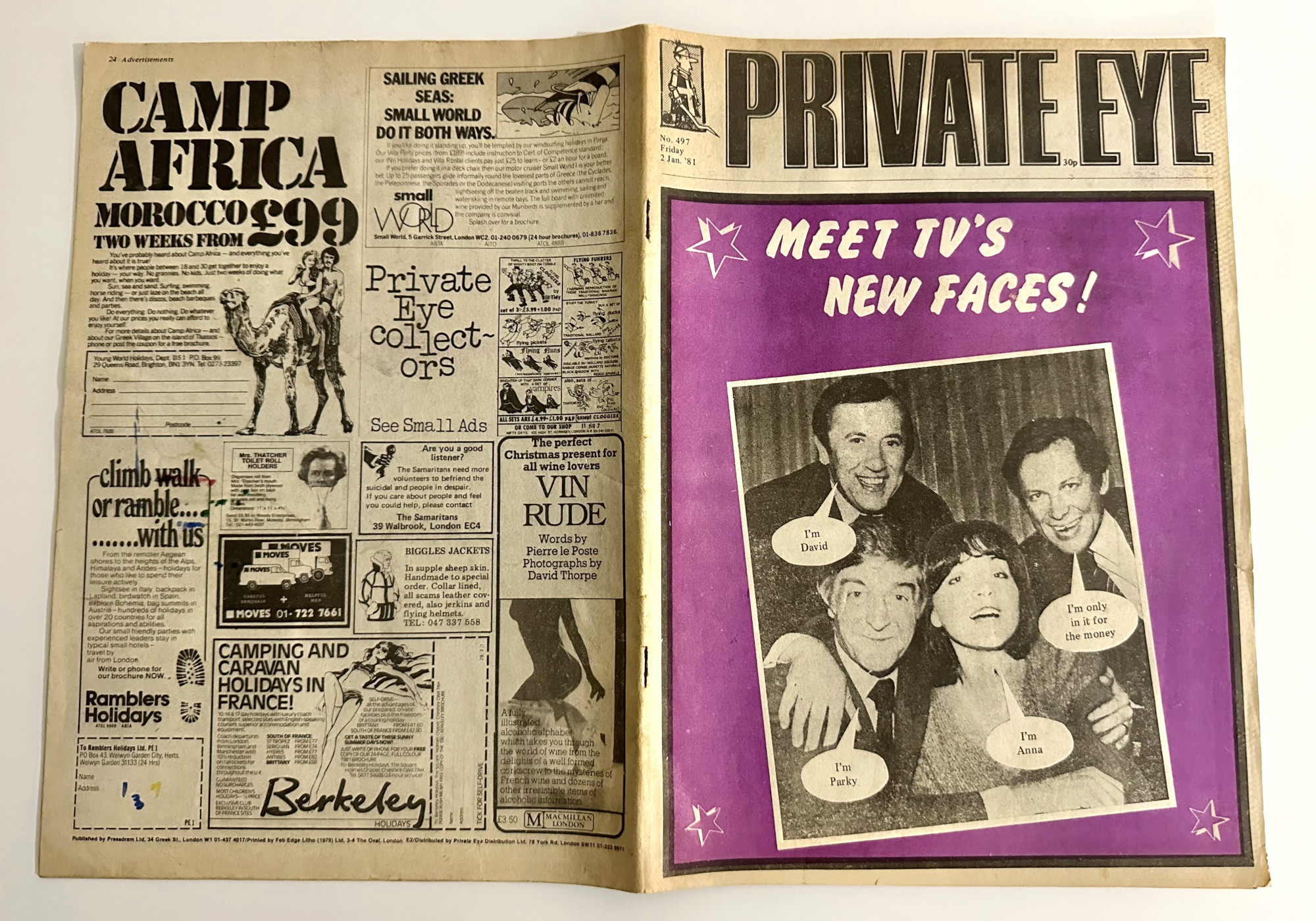

Not quite. The above cover doesn’t appear in Private Eye‘s cover archive. But Issue 497, dated the 2nd January 1981 – just a month before the studio date – looks rather suspicious:

That purple background is very distinctive. Which gave me ideas. But there was only one way to know whether I was right. Luckily, the back page of the magazine is very prominent in the episode as well, with the obvious wording of CAMP AFRICA in the top left.

A quick eBay later, and I held a copy of Issue 497 in my sweaty, desperate hands. Was my gut feeling correct?

Yes indeed. The prop department simply got a recent issue of Private Eye, stuck a new picture on the front over the old one, and job done. Lovely.1

The question is: why exactly did Yes Minister bother to change the picture? Is it because the original cover has TV-am stars on? Could they not get the rights? Or did the Beeb literally not want to advertise ITV?

It’ll be something like that, anyway. But I would suggest there’s another reason why it makes sense to have a mocked-up Private Eye cover. The world of Yes Minister isn’t quite our world. Sure, there are newspapers dotted around the series which have real-life headlines, but they aren’t usually plot-relevant props. As soon as something gets drawn into the story, it makes sense for the issue of Private Eye to not be a “real” one. Things are supposed to be slightly askew. ↩

On the 23rd December 1982, BBC2 broadcast the final episode of Series 3 of Yes Minister. Titled “The Middle Class Rip-off”, it’s an amusing satire on arts funding, and the nature of “high” culture and “low” culture.1

SIR HUMPHREY: The point is, suppose other football clubs got into difficulties. And what about greyhound racing? Should dog tracks be subsidised as well as football clubs, for instance?

BERNARD: Well, why not, if that’s what the people want?

SIR HUMPHREY: Bernard, subsidy is for art. For culture. It is not to be given to what the people want. It is for what the people don’t want but ought to have! If they want something, they’ll pay for it themselves. No, we subsidise education, enlightenment, spiritual uplift. Not the vulgar pastimes of ordinary people.

You can probably guess which side Hacker is on.

HACKER: Why should the rest of the country subsidise the pleasures of the middle class few? Theatre, opera, ballet? Subsidising art in this country is nothing more than a middle class rip-off.

SIR HUMPHREY: Oh, minister! How can you say such a thing? Subsidy is about education. Preserving the pinnacles of our civilisation! Or hadn’t you noticed?

HACKER: Don’t patronise me Humphrey, I believe in education too. I’m a graduate of the London School of Economics, may I remind you.

SIR HUMPHREY: Well, I’m glad to learn that even the LSE is not totally opposed to education.

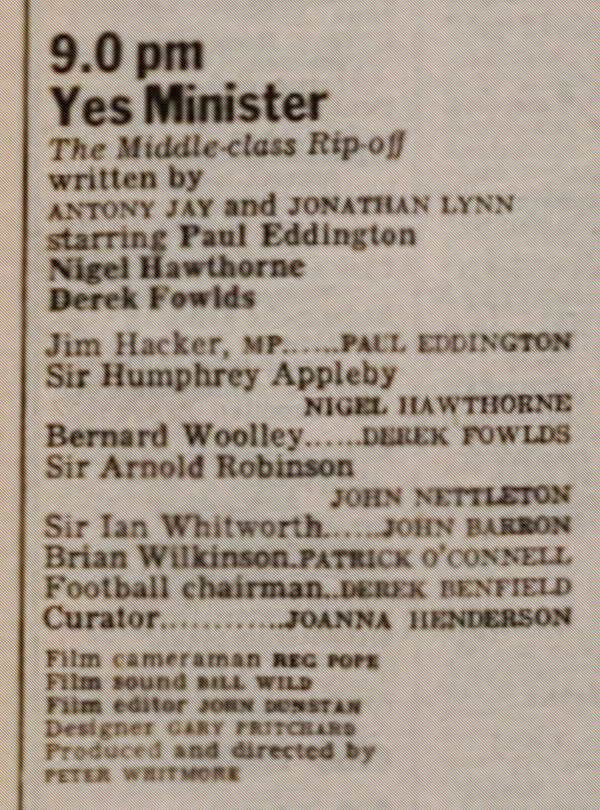

Very droll, Humphrey. Still, the rights and wrongs of funding for the arts isn’t our big interest today. Instead, I want to look at the Radio Times capsule for the episode. Which features something rather unusual.

Take a look at those names. Eddington, Hawthorne, Fowlds: check. And John Nettleton, John Barron, Patrick O’Connell, and Derek Benfield: check. But what about Joanna Henderson, playing the Curator? She’s not in the episode at all. Nor is she in the end credits. What gives?

To answer that, I have to take you on a little expedition. And to tell the tale properly, we have to go right back to 1979.

For an alternative – and rather more negative – view of the episode, read Graham McCann’s A Very Courageous Decision: The Inside Story of Yes Minister, a book which comes highly recommended. ↩

Much as I love Jonathan Lynn’s Comedy Rules: From the Cambridge Footlights to Yes, Prime Minister, it seems that every time you poke it, another inaccuracy falls out. I’ve already talked about a certain set of Evening Standard reviews of Yes Minister. But that’s far from the only problem.

Let me quote that section of the book again.

“No one took much notice of the second episode, but everything changed after the third week. This sudden surge of enthusiasm was the result of a lengthy article by Roy Hattersley in the Spectator. Hattersley was Deputy Leader of the Labour Party at the time and, like Jim Prior in the Tory Party and Jim Hacker in our series, was a centrist politician who could have belonged to either party. Hattersley described everything that the show had shown so far, confirmed that this was exactly what had happened to him when he first became a minister, and asked how on earth did we know?

Hattersley’s article galvanised the political press. Suddenly political correspondents took up the show and editorials started to be written about it. The TV critics, late to the party, jumped on the bandwagon, and after the fourth episode the critic from the Evening Standard told his readers that Yes Minister was an excellent comedy show and he had said so from the start. He hadn’t.”

As well as misrepresenting the Evening Standard reviews, commenters here were quick to notice other errors. David Boothroyd correctly points out that Hattersley only became Deputy Leader in 1983; it was Michael Foot in the role at the time of Yes Minister‘s first series. Worse, even the referenced article by Hattersley is incorrectly attributed: Simon Coward points out that there’s no evidence of such an article in The Spectator around this time.

Luckily, I have very good readers who do all my work for me. A bit more digging from Simon revealed that the article wasn’t in The Spectator at all; it was in The Listener instead. Silly similar syllable sounds. And then your friend – and indeed he’s my friend as well – John Williams kindly bunged me a copy of the whole article.

Titled “Of Ministers and Mandarins”, and published in the 20th March 1980 issue of the magazine, this was clearly written after the third episode of the series was broadcast: “The Economy Drive”, on the 10th March. It represents one of the very first serious pieces of analysis of Yes Minister – perhaps the very first – and so is an important document in our understanding of the initial reaction to the show.

It seems worth, therefore, replicating the article in full. Take it away, Roy Hattersley.

Jonathan Lynn’s Comedy Rules: From the Cambridge Footlights to Yes, Prime Minister is a slightly odd tome. Part autobiography, part an attempt to nail down the rules of comedy – while admitting that any such attempt is doomed to failure – it does feel like it would occasionally benefit from a little more focus. On the other hand, I found myself nodding along vigorously to pretty much every single page.

For instance, when talking about Yes Minister and Yes, Prime Minister:

“The series eventually ran from 1980 to 1988 but was not about the eighties. It was devised in the seventies and reflected the media-obsessed politics of the Wilson/Heath/Callaghan years, not the conviction politics of Margaret Thatcher. It was actually much closer to the politics of the years that followed, the years of Major, Blair and Brown. In any case, there is a timelessness about good comedy: the pleasure and excitement of recognition are not rooted in a particular time or place. Humanity remains constant.”

This dual nature of what comedy can be is key: it can be ostensibly linked to a particular time, and yet still leap easily across the years. I always shake my head in dismay when people tell me how easily comedy dates. Comedy is usually about people, and people don’t change either as much or as quickly as many would like to think.

SIR ARNOLD: What about the DHSS? John?

SIR JOHN: Well, I’m happy to say that women are well-represented near the top of the DHSS. After all, we have two of the four Deputy Secretaries currently at Whitehall. Not eligible for Permanent Secretary of course, because they’re Deputy Chief Medical Officers and I am not sure they’re really suitable… no, that’s unfair! Of course, women are 80% of our clerical staff and 99% of the typing grade, so we’re not doing too badly by them, are we?— Yes Minister, “Equal Opportunities” (1982)

BARBIE: Are any women in charge?

MATTEL CEO: Listen. I know exactly where you’re going with this and I have to say I really resent it. We are a company literally made of women. We had a woman CEO in the 90s. And there was another one at… some other time. So that’s two right there. Women are the freaking foundation of this very long phallic building. We have gender neutral bathrooms up the wazoo. Every single one of these men love women. I’m the son of a mother. I’m the mother of a son. I’m the nephew of a woman aunt. Some of my best friends are Jewish.— Barbie (2023)

Humanity remains constant indeed. Especially the terrible bits. Which is what an awful lot of comedy is about.

Anyone up for yet more production fun with Yes Minister? Of course you are.

Take a look at the below scene from the Series 3 episode “The Challenge”, broadcast on the 18th November 1982. Hacker is in a TV studio for a BBC documentary about civil defence, about to be interviewed by Ludo. Sorry, Ludovic Kennedy.

Spot anything interesting about the above scene? Take a look at the very opening shot. If you look carefully at the top of the interview set, you can see that it’s just a couple of green walls placed in front of one of Yes Minister‘s “real” sets!

Which one? I highly suspect that it’s the dining room set – there is a glimpse of the odious framed wallpaper at the top:

Regardless of any peeping bits of set, it’s a great bit of production design by the wonderfully-named Andrée Welstead Hornby. With a couple of green flats, and judicious use of the side of Studio 6 at TV Centre, you have a completely convincing setup, for very little money indeed. Because TVC was used to make all kinds of programming, it was very easy to simulate all kinds of programming as well.

Sometimes, as with Python, it’s easier and more effective to do your satire from the inside.

This point extends beyond the sets. There’s one more bit of fun to be had with this scene. Let’s take a look at the production paperwork for the episode; buried deep within it is the following:

IN VISION STAFF

BRIAN JONES – Production Manager, Light Entertainment Comedy Tel.

ANDREW MOTT – Camera Operator, Technical Operations

The above two names aren’t actors. These are actual BBC staff, who appear in-vision during the interview sequence. And who must have worked on Yes Minister as the actual Production Manager and a Camera Operator respectively.

Sadly, the only camera-related credit in the end credits is Peter Ware as Senior Cameraman. But if we check the Production Manager credit:

Much like the wall of TC6, why not use what you have already, for added verisimilitude?

Now come on someone, write a sitcom which involves a BBC Network Director in a bit part. I want my own little moment of glory.

On the 15th February 1988, the first episode of Red Dwarf aired on BBC2. I had no idea about it.

On the 7th January 1994, the first episode of Red Dwarf aired on BBC2 for the second time. I became obsessed with it.

On the 25th August 2023, the first episode of Red Dwarf aired on BBC2 for the seventh time.1 I prepped it for TX.

I usually write BBC2 for the channel pre-1997, and BBC Two for the channel post-1997, as per the branding guidelines. But that got really irritating swapping between the two with this article, so I’ve stuck to BBC2 for everything here. ↩

Of all the books I’ve used for research on Dirty Feed over the years, I’ve rarely quoted from one as extensively as I have from Tooth & Claw: The Inside Story of Spitting Image (Faber, 1986). It is, for me, the absolute gold standard of any behind-the-scenes book. Not just because it’s fascinating – although it clearly is – but because it’s goddamn accurate.

This is a constant bugbear of mine. While researching the Doctor at Large episode “No Ill Feeling!” for this article in 2019, it was notable that certain books managed to get both the TX date and title of the episode incorrect. Which is kinda the basics, really. Tooth & Claw, meanwhile, manages to correctly cite which exact episode certain sketches appeared in, which gives you confidence in the rest of the book. And making sure such things were correct was a lot harder in 1986 than it is now.

Anyway, surely everybody loved the book at the time of its release too? Sadly not. Thanks to Sham Mountebank, who pointed me towards the following contemporary review of the book, from short-lived LM magazine.1

Not Living Marxism; this was a project from the publisher of Crash & Zzap!64, which folded after four issues. ↩

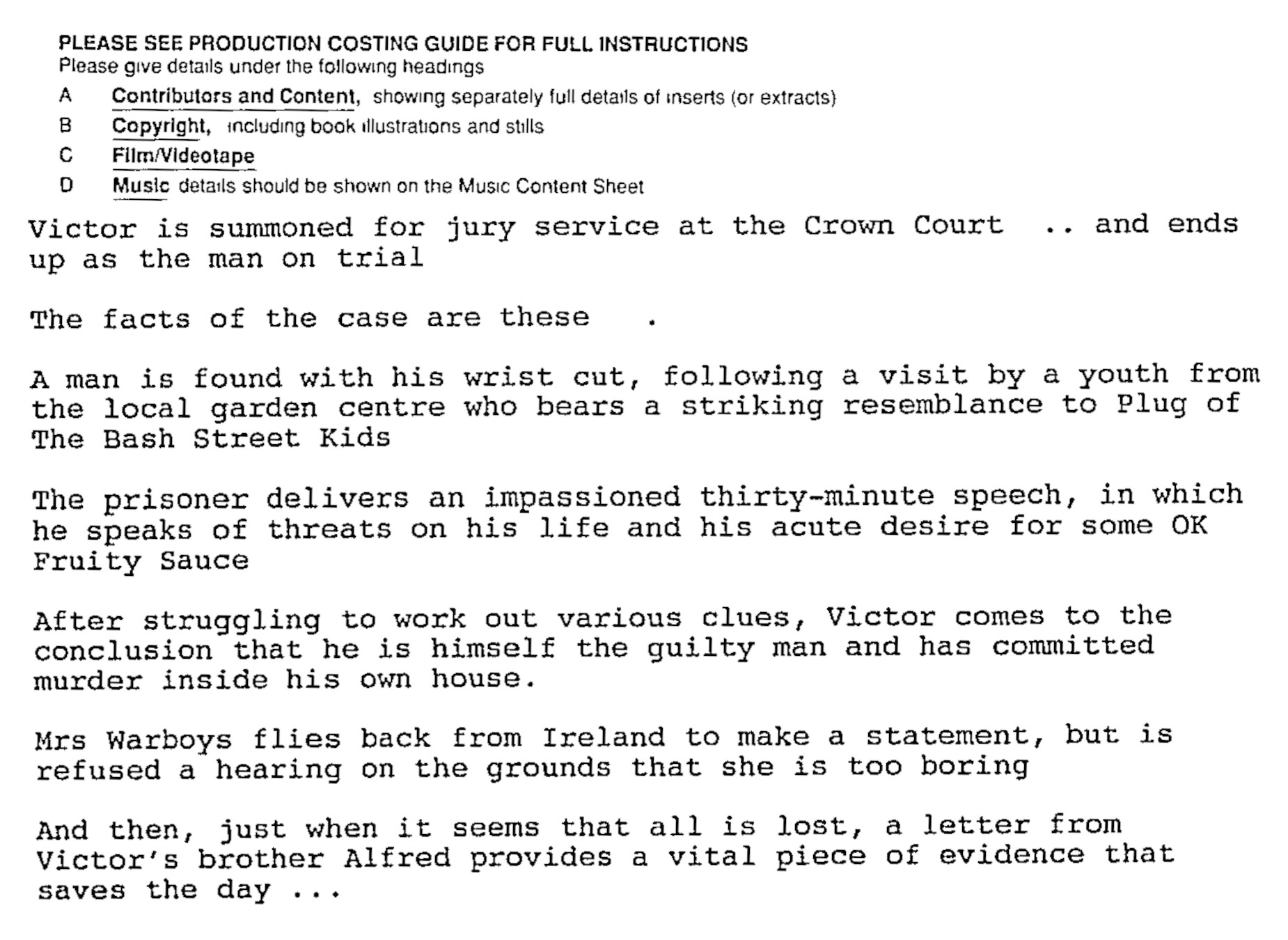

Sometimes, I come across something fun in my research which I just have to share. The following is the official synopsis for the famous One Foot in the Grave episode “The Trial”. It is, frankly, difficult to imagine it being written by anyone other than David Renwick.

In comparison, the Radio Times capsule for the original broadcast of the episode on the 28th February 1993 is simply the following:

“Popular sitcom about a grumpy old man for whom nothing ever seems to go smoothly. Victor is called up for jury service and ends up as the man on trial.”

Which essentially only uses one line of the full synopsis.

That full synopsis is fun for a number of different reasons. Most obviously, it shows Renwick’s thought process for the episode: that Victor is both awaiting a real trial, and actually experiencing a mock trial. This does eventually become text in the episode – killing a woodlouse and being sentenced to death – but it’s all done fairly subtly. It being stated so obviously is its own joy.

But my favourite line in that extended synopsis is the following:

“Mrs Warboys flies back from Ireland to make a statement, but is refused a hearing on the grounds that she is too boring”

Which is, obviously, very funny indeed. But I was especially reminded of the line when reading of the sad death of Doreen Mantle the other day.

Because the thing Doreen did so brilliantly in One Foot in the Grave is taking what could have been an immensely irritating character who you were desperate to get rid of, and turned her into a delight to watch. To the point where, even when you’re watching Richard Wilson’s 30-minute tour de force monologue, Mrs Warboys is right there in your head anyway. And part of the reason “refused a hearing on the grounds that she is too boring” is funny is because it conjures up Mantle’s confused, tedious face.

Her performance manages to echo not only into an episode she isn’t actually in, but a text description of an episode she isn’t actually in. I’m not sure you can get any more captivating.