For more on this BBC100 series of posts, read this introduction.

Right at the beginning of this series of articles celebrating the BBC’s centenary, we looked at Nineteen Eighty-Four, a drama broadcast live to the nation some seventy years ago. Why was it broadcast live? Because that’s just how things were done. Videotape was still in its infancy, and not in use by the BBC at all back in 1954.

But as television matured, and videotape became standard, making fiction this way slowly fell out of favour. There were still plenty of live programmes, sure – sport, news, entertainment – but drama fell by the wayside. Of course productions wanted more control over what they were making, and once it became easier and cheaper to pre-record everything, that’s exactly what they did. Besides, what did being live add to the experience anyway?

The answer is: rather a lot. And sure enough, slowly but surely, we began to see a revival. Live drama, not made because it was the only possible way to make something, but because it was a fascinating way to make television in its own right. We just needed some distance in order to see it.

The clear catalyst for this revival was the American medical series ER, and their 1997 episode “Ambush”. Charting a day in the life of the unit through the lens of a PBS documentary film crew, this was a stroke of genius for their big experiment: this kind of story meant that the show didn’t need to replicate its traditional look. Instead, the handheld documentary style was the point, and its rough and ready nature could work in the show’s favour.

Three years later, for Coronation Street‘s 40th anniversary, ITV decided to pull a similar trick. After all, its very first episode in 1960 had gone out live – what better way to celebrate than to replicate how the show used to be made? This time, there was no documentary cheat: the show had to look like a normal episode. Still, with Coronation Street still being shot multi-camera as it always had been, rather than in a more cinematic single-camera style, such cheats weren’t necessary. Any given scene was essentially shot the same as it always was: it was doing those scenes one after the other without a recording break which was the real work. And, of course, getting just one chance to get it all right.

The episode was a success, and both sides of the Atlantic seemed eager for more. In the same year, CBS broadcast Fail Safe starring George Clooney; a one-off drama rather than part of a continuing series. It seemed obvious this was where UK television would go next. And yet nobody quite seemed able to take the plunge. ITV aired a live episode of The Bill in 2003, to celebrate 20 years of the police drama. But when would someone in the UK dare to do a standalone live play?

That moment finally came on the 2nd April, 2005. As the continuity announcer intoned:

“Live drama on the BBC for the first time in over 20 years, here and now on BBC Four. Not for the faint-hearted – on the sofa or in the studio – thrills and chills, and some flashing lights, as Jason Fleming, Mark Gatiss, and David Tennant star in The Quatermass Experiment.”

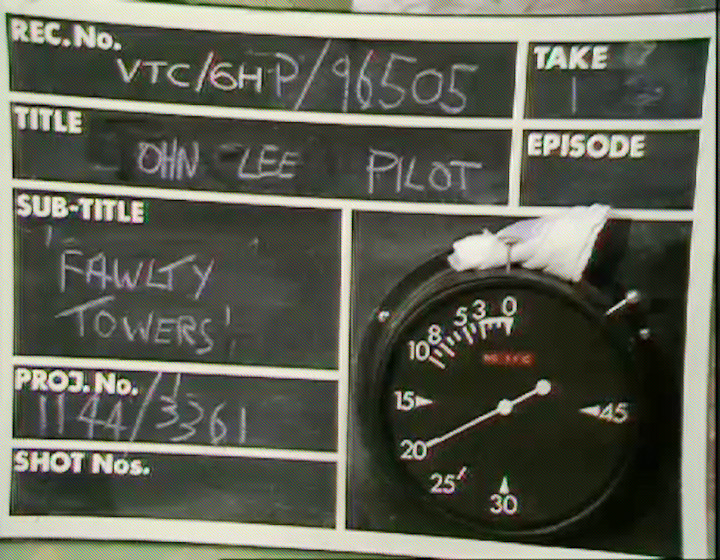

The Quatermass Experiment was the perfect choice. The original serial was broadcast live on the BBC in 1953, and – like the Nineteen Eighty-Four adaptation – was written by Nigel Kneale. It was the first science fiction series specifically written for an adult British television audience, it being neither aimed at kids, or an adaptation of a previous work. And while it’s gone down as a seminal piece of television, and was later adapted into a film, only the first two episodes of the original serial survive. The last four aren’t even lost – they were simply never recorded in the first place, the results of the experimental process of recording the first two being deemed unsatisfactory.

Inevitably, the 2005 version is slightly condensed; the original serial was three hours long, while the 2005 remake is a shade over an hour and a half. But the increased pace of the production means that far less is cut than you might think, and indeed the original scripts were used as the basis for the adaptation. Moreover, the central story of an alien presence travelling to earth via a manned mission to space, and the horrific mutation of the single remaining crew member, remains as chilling as ever. The biggest change from the original production is swapping the original climax at Westminster Abbey for one at the Tate Modern. Ostensibly done for production reasons, it makes a certain amount of thematic sense too; many people in 2005 would find the Tate Modern rather closer to their spiritual centre.

Indeed, the fascinating thing about watching the production, much like Nineteen Eighty-Four, is just how quickly you forget that the programme is live. Oh, it’s there in the back of your mind, sure. But the show isn’t interesting because it was live. It’s interesting and it was live. Watching a production performing a high wire act of keeping a live drama from collapsing around its ears doesn’t keep your interest for an hour and a half. Story and characters do. Same as it ever was.

Instead, the effect is more subtle; the live nature gives the drama a life that is difficult to replicate any other way. Characters speak with an urgency and a reality which is sometimes difficult to achieve when you’ve got a whole day to get it “perfect”. Perfection in drama can be a fool’s errand; if every cut is perfect, sometimes all you can feel is the artifice. Artifice is not always a bad thing in drama, but neither is it a universally good thing either. The trick, surely, is to have a range of approaches to our television.

Inevitably, there was the odd issue with the production. Pope John Paul II had the temerity to die that day; a caption was placed over the programme pointing viewers to the BBC’s news channel. (It’s difficult to imagine similar news warranting such a caption today.) One scene ended with an unscripted off-screen crash. And poor Adrian Bower as journalist James Fullalove forgot his lines during one scene, resulting in a few agonising seconds of the programme going entirely off-piste. But overall, it was an absolute triumph.

And yet, if you buy the programme on DVD today, none of the above issues are present. Sure, the caption about the Pope was put on by BBC presentation rather than the actual production; you wouldn’t expect that to be included. But the crash has mysteriously gone, and the scene where Bower dried has been entirely replaced with a recording from the dress rehearsal. More seriously, the entire programme has been recut; shots changed, removed, or trimmed. It is no longer a representation of how the programme looked on the night. If you watch that DVD, don’t be fooled: despite the caption at the beginning claiming to be a live production, by the time the editors had done their work, that simply isn’t true any more.

Sadly, our fabled revival of live drama in the UK seems to have stalled somewhat as well. In 2015, I had the pleasure of being in BBC presentation for a live episode of EastEnders; the same year, ITV did a beautiful live version of The Sound of Music. But since then, things have tailed off. The BBC’s centenary would have been the perfect chance to put on a production much like the 2005 Quatermass; perhaps an adaptation of its sequels Quatermass II and Quatermass and the Pit? Or perhaps, God forbid, something entirely new? Instead, we got nothing.

Oh, there have been rumours. Casualty was supposed to do a live episode to celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2016; this never happened, and was replaced by a decidedly non-live episode in 2017, albeit done in one take. Over on ITV, there were rumours of a live episode of Emmerdale last year to celebrate the show’s 50th anniversary, after the success of the one for their 40th in 2012; instead, the show’s executive producer Jane Hudson gave interviews to the press specifically explaining that they wouldn’t do another.

Instead, over the past few years, comedy seems to have taken up the space. Mrs Brown’s Boys did live episodes in 2016 and 2021; Not Going Out did a live episode in 2018, as did Inside No. 9. The latter was certainly more of a drama than a comedy, but the other two examples are audience sitcoms; and specifically, the kind of audience sitcoms where, if things go wrong, it doesn’t matter. Both Brendan O’Carroll and Lee Mack are the kind of performers who can make hay out of mistakes. The potential destruction of the show’s reality is a boon for them, not something to fear. In today’s social-media-driven world, where mistakes by actors can easily be amplified, maybe it’s all eminently understandable.

So yet again, TV takes the safe way out, and everyone’s happy. And something like 2005’s Quatermass becomes not part of the new vanguard, but of something that we can happily place in the past. Again.

Until next time?

Read more about...

bbc100, live television, quatermass