Sonic Adventures (Act 2)

|

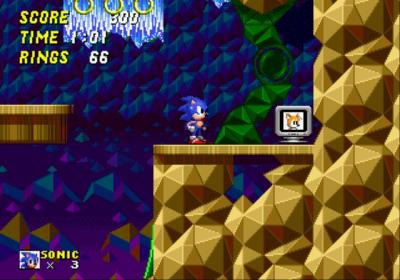

While Sega Japan was happy to allow a more experimental approach to their new character from a different team, Sega of America was under no such illusions. The 16 Bit console was selling like hot cakes, and the reason was obvious. For this reason, they took the re-hired Yuji Naka and a handful of other veterans of the original title and placed them in charge of a team of rookie developers at their “Sega Technical Institute”. Although given an extremely short development period, Sonic 2 managed to become the definitive game in the series, providing the title that everyone thought the original had been. Recognising that the locations on offer had been one of the main draws of the first game, the sequel offered a greater number of shorter levels, with the number of ‘acts’ reduced from three per stage to two. The introduction of the standing-start Spin Dash maneuver was also emblematic of a faster-paced and more immediate venture.

Another change made was in the light of the public’s attachment to the character. The only piece of active storytelling in the first game, where Robotnik unexpectedly drops his enemy back into the hazards of the Labyrinth Zone from the Scrap Brain final level, was considerably expanded upon. The game shows how Sonic moved between the final set of locations, using the newly introduced Tornado biplane to attack the Wing Fortress and then hitching a ride to the Death Egg, the ultimate weapon that Robotnik had been constructing throughout the game. Technical limitations forced the discarding of an earlier cut-scene, in which Robotnik would have demonstrated the Death Egg’s power by an orbital strike destroying the Metropolis Zone. Sonic and Tails would then have to fight through the ruins of the city to reach the Tornado. Sadly, the Sonic 2 engine wasn’t up to the task of coping with the palette swap that would be needed for the resulting Genocide City Zone. The idea was dropped and the completed level designs were used for form a third act of the Metropolis, with the mid-level apocalypse idea later remounted as Sonic 3’s Angel Island Zone.

|

Speaking of the fox, much of the expansion of the gameplay concepts was linked to Miles ‘Tails’ Prower (it surprises me to this day how many people don’t notice the truly terrible pun in the character’s name). The arrival of Sonic’s mechanically minded sidekick was a clear statement of intent, expanding a solitary experience into one that featured anytime drop-in co-op, to use today’s vocabulary. Having a second player controlling the fox was highly advantageous, as his effective imortality meant that he could bear the brunt of Robotnik’s improved array of badniks. This was just the tip of the iceberg, however, compared to the inclusion of the most comprehensive split-screen versus mode the series has yet seen. The contest pitched Sonic and Tails against each other across a number of stages, with the eventual victor judged on a far broader array of grounds than a simple race. Some people believe that game to have invented the split-screen technique, but this has yet to be verified.

There’s a few interesting artistic decisions, as well. The Egg-omatic (the Europe name for Robotnik’s vehicle) has a more Heath Robinson feel than in its other appearances, being visibly cobbled together from various components. In contrast to the semi-coherent journey around South Island that the first game offered, the levels here are ordered for visual and gameplay diversity, with the opening idyllic Emerald Hill being followed immediately by the Chemical Plant. The originality of the level concepts is maintained by the slight twists that are placed on the core ideas that return from the first game. For example, Emerald Hill has a notably more tropical feel that the original’s Green Hill, and the Metropolis is less industrial and more of a city than its Scrap Brain predecessor. The largest shift was toning down the surrealism of the Special Stage, with the technical enhancements meaning that the game didn’t have to resort to such cheap tricks to given a severely different feel to the areas from which Sonic recovers the Chaos Emeralds. A more tangible reward for recovery of the gems was adopted this time around in the form of Super Sonic, but the indestructible yellow version of the hedgehog has always been underplayed in the games. While the additional fiction versions of the character have seen him both elevated to near omnipotence and reduced to an blood-thirsty psychopath, Sonic Team seemed content to treat the creation as simply a more powerful version of their hero, being a hidden bonus for dedicated gamers.

Although Sonic The Hedgehog 2 rightly enjoyed incredible sales figures, it’s important to remember how near-to-the-wire its release was. More than any other Mega Drive Sonic, its development was characterised by stops and starts and the Sonic fan community has been discovering unfinished betas for years, the most famous of which includes a nearly complete additional level, in the form of the Hidden Palace Zone. It was this stormy experience that would lead Yuji Naka and his Japanese colleagues to demand major changes to the structure of Sonic Team before they undertook development of the hedgehog’s next major adventure.

|

A slightly different approach was taken for the 8-bit versions of the second game, with the product released being obviously an entirely different title. The plot centred on Robotnik having kidnapped Tails, explaining the fox’s non-playability, and Sonic is charged with collecting the Chaos Emeralds in order to rescue his sidekick. On paper, the game looks like a ‘fixed’ version of the first Master System release, with its engine rebuilt to allow the character to move at greater speed. Even minor niggles have been addressed, with the sprite’s trainers corrected from brown to red. This good work is unfortunately undone by a rock-hard difficultly level, which presumably stemmed from a rushed development and lack of time to balance the game, and some horrid art direction. The game’s style lacks crispness, with the sharp main sprite contrasting with the muddy and insipid environments he progresses through.

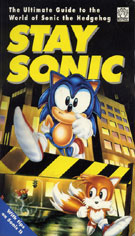

In terms of creative control of the franchise, this period is one of the most interesting. With the first game, Sega Japan effectively offered the character to its subsidiaries to ‘sell’ as they saw fit, according to the nature of their territory. Although some ideas occurred independently to all of the creatives involved worldwide, such as Sonic’s ‘power sneakers’ having a friction-reducing function to stop the character setting his feet alight, this notions were the exception. The result produced some interesting quirks, such as the Robotnik/Eggman discrepancy. Sonic Team named their recurring villain Eggman, but the company’s western arms felt that a more sinister moniker would have greater appeal, and so dubbed the character Robotnik for the (earlier) Pal and US release of the game. When Sonic Team took creative control of the franchise in 1998, a brief attempt to reconcile the situation failed, and the developers bit the bullet and standardised the name worldwide. Most fans have accepted the issue with a shrug of the shoulders, and Sega Europe have now begun to add “A.K.A. Dr Robotnik” on the end of the brief biography of the character in the games’ manuals. Back in 1992, however, anything went, and Sega Europe was free to construct their own conception of the character, formalised in the psuedo-factual book ‘Stay Sonic’.

|

The attitude towards ‘origin stories’ for ongoing fictional characters is an interesting cultural dichotomy between western and Asian nations. It’s hard to think of any superhero over here that isn’t defined by how they obtained their powers, but the Japanese tend to show little interest in this aspect, being more interested in the finished article. Sonic Team felt no need to furnish their character with a back-story, being content to just present the hedgehog’s adventures as a fait accompli. Sega Europe, on the other hand, crafted a detailed tale that not only explained why Sonic is blue, but the driving factor behind Robotnik’s insanity and even the reasons why the pair’s world is covered in gold rings and rather curious television monitors. The tale of Dr Ovi Kintobor and his ill-fated bid to rid Mobius of all evil formed the bulk of ‘Stay Sonic’, with the book rounded out with tips on both incarnations of Sonic 2 and shorter chapters which analysed the various badniks and dealt with matters such as how the hedgehog first met Tails. The most striking feature of the European conception of Sonic is its literality, taking the artistic style of the games as gospel in the absence of creative input from the character’s creators. It was a sensible approach, perfectly chiming with the views of the games’ younger players, whose imaginations would be most fuelled by the titles. The European Sonic gave the writers of additional fiction much material to work with, and remains fondly remembered.

The crowning glory of the Europe Sonic continuity came from a third party, however. You thought I was joking when I mentioned novels in the preamble? A total of four books were released by Virgin publishing, all running to about two hundred pages, from a collective of three writers including James Wallis. Published under the name Martin Adams, they come in at the top end of the ‘young adult’ category, mainly due to the complexity of plotting and insistence on occasionally over-reaching themselves in terms of content- there’s a particularly vividly described passage in which Sonic spin-attacks a zombie. Having expected that his opponent would actually be revealed to be a robot, he’s somewhat nonplussed by the shower of offal which results. The books are arguably the most faithful adaptation of the Mega Drive games imaginable, using the architecture of the titles taken literally. This means that the planet Mobius is actually split into zones, which can only be moved between at certain key points. Unlike the Japanese version of Sonic, the character is resolutely not a drifter, and his main motivation in each of the books is to save his friends, who are drawn from the list of names for the animals that populate the games, as devised by Sega Europe. The only original addition to the regular cast of good guys is Mickey the Monkey, a dodgy cockney engineer who foreshadows the reconceptulisation of Tails as a techno genius. Robotnik gains his obligatory robot sidekick, although Eggor’s true nature turns out to be a plot point of one of the titles. Speaking of the scientist, “Adams’s” take on the character is truly magnificent, managing to entertain through incompetence without ever loosing his capacity to create genuine menace.

|

Aside from the first book which focuses solely on Robotnik’s development of a new weapon, the titles each took a sci-fi stable as their inspiration, consisting of a refreshingly complex time-travel tale, a cyberspace adventure and a horror epic that follows from Robotnik’s branching out into genetic engineering. At the time, the quality of the books was unprecedented, and even now they mount a reasonable challenge for the title of the best piece of Sonic additional fiction. Although they don’t provide a high concept for the character, their selfless adherence to the tropes of the games oozes charm, and ‘Adams’ always judges exactly the right moment to break the fourth wall, usually by having Sonic wryly commenting on proceedings. The writer’s ability to take each of the simple tropes he borrowed and make them fit perfectly into the European Sonic-verse is magnificent, and if you have even a passing fondness for the early nineties version of the character, it’s worth throwing a few quid Amazon’s way.

Also from the same stable came a series of “choose your own adventure” books, which sadly lacked the wit of their conventional prose siblings. You can’t fault them for the accurate reconstructions of the world of the first two Mega Drive titles, but there isn’t the sense of mischief that makes the novels such a joy to read. The first two releases are probably the best of the bunch, with the second book undertaking an impressively complex simulation of the videogames’ mechanics, although keeping track of both Sonic and Tails’ stats can become challenging. Later books such as The Zone Zapper and Sonic Vs Zonik (an early spin on the Metal Sonic concept) are faithful to the ethos of the series, but don’t make much of a contribution of their own.

Next Time: After spending so much time in Europe, we head across the pond to see how Sega of America was marketing the character, before Sonic 3 comes and raises the bar for all 2D platform games.

About this entry

- By Julian Hazeldine

- Posted on Sunday, June 21 2009 @ 7:11 pm

- Categorised in Games, Analysis

- Tagged with sonic the hedgehog, Sonic Adventures, Sega

- 4 comments

Very strong. I’m now hugely interested in getting those novels, as they sound aces.

By Jonathan Capps

June 21, 2009 @ 9:42 pm

reply / #

>”it surprises me to this day how many people don’t notice the truly terrible pun in the character’s name”

It suprises *me* even more so that there are *still* people who insist that Tails is - in actual fact, a squirral, despite the fact he looks nothing like one, and offically reffered to as a fox on several occasions.

By MJNSEIFER

June 21, 2009 @ 10:08 pm

reply / #

I misread Martin Adams as Martin Amis at first. That would have been a thing.

By Applemask

July 16, 2009 @ 12:36 pm

reply / #

Actually, Applemask, the pseudonym was originally going to be ‘Martin Ames’. Then we figured we’d probably get sued, and changed it.

By James Wallis

August 17, 2009 @ 11:30 am

reply / #