Sonic Adventures (Act 7)

|

Once prototype Dreamcast development kits became availible, Sonic Team frantically began work on Sonic Adventure for the system’s launch. This is best thought of as the last of the ‘first wave’ of the series, with character designer Naoto Oshima leaving Sega to start his own company on completion of the title. (Of the hedgehog’s original creators, only Yuji Naka would remain with the Team for the second phase of Sonic’s life.) The game presented a competed version of the prototype seen in Sonic Jam, with addition of the homing attack that makes the hedgehog’s combat gameplay work in 3D. It’s hard to shake the feeling that one of the reasons why Adventure moved to the later hardware concerns the size of the levels, both in terms of game disk space and memory. During an interview shortly before the launch of the game, Naka commented that the scale of the maps he had to create was the greatest problem in the game’s development. Although the Sonic World prototype had coped reasonably well with a Mario 64 sized environment, the character had noticeably lacked speed, highlighting the need for the vast environments that Adventure introduced. It was this effort which lead to the introduction of other playable characters to the game, in order to allow players to note at leisure the detail and ingenuity which had been channelled into areas which they would initially just speed past. Adventure took the approach of splitting the story between the characters, with each having their own perspective on events- interestingly, shared cut-scenes in Adventure feature fractionally different lines of dialogue when participated in as different characters, both easing monotony for the player and giving the impression that each participant remembers the events slightly differently. Gameplay wise, the Sonic-level settings are slightly repurposed, with Amy and robot E102 effectivly having unique environments to suit their styles of platforming, while Knuckles undertakes a semi-random treasure hunt, using his exporation-based abilities to move around existing zones. Big the Cat has a fishing-based minigame, while Tails draws the short straw. Flying was obviously too challenging a mechanic for the team to fully address, so the fox is limited to racing his hero through short sections of Sonic’s levels. Completing each character’s game unlocks the final section, in which control of Sonic is resumed for the final battle. This approach to storytelling has since become archetypal for Sonic games, infuriating those who only wish to play as the main character. Regard the other takes on the levels as bonus content, though, and it’s hard to begrudge the developers’ wish to show off the areas they have created.

One of Oshima’s final tasks while working at Sonic Team was to redesign his creation for the more powerful hardware. The artist chose to make the hedgehog even more stylised, streamlining him and exaggerating him further. The innocent look of the Sonic 1 design was replaced by a vicious grin, with the addition of green pupils to the character reflecting a general increase in detail of the design. This approach was then rolled out across the remainder of the returning characters, although more significant changes were made to Amy and Dr Robotnik. The female hedgehog was completely redesigned, being drastically aged and given a simplified red dress. Oshima’s work on the mad scientist finally banished the memory of the AoStH version, giving the character a red coat with a slightly military air, as well as goggles to emphasise his engineering experience. With minor tweaks, these versions of the characters have been used ever since on all formats. The Japanese teaser campaign for the game’s announcement in summer 1998 emphasised the redesign, using the image of the hedgehog’s new teeth and eyes against a black background.

|

The game’s scenario was also a trendsetter, with Sonic’s battle against Robotnik’s new ally, the water elemental Chaos, being heavily inspired by a real-world location. Sonic Team undertook a fact-finding trip to South America, and much of this came through in design of the Mystic Ruins adventure stage and the Lost World Zone action area. Since then, Adventure 2, Sonic [2006] and Sonic Unleashed have all placed the hedgehog in an environment derived from a real-world location, as a means of avoiding the diminishing returns of the Mega Drive-inspired fantasy environments. This fits in very well with the emphasis the series has always placed on the design quality of its levels as a means of capturing potential players’ attention. Adventure started a trend towards the idea of Sonic games as a holiday for their players, and this concept has continued through the core series to this day. Even the parts of the game outside of the Mayan setting hint at reality, with the crash barriers at the side of signature action stage Speed Highway a familiar sight to anyone who’s experienced Tokyo’s road network.

|

Sonic Adventure also set a trend for the reminder of the series through its soundtrack release. A single CD containing the game’s vocal songs formed the initial release (i.e. the main theme and those for each of the playable characters), and was followed a couple of months later by a two disk set which contained all other tracks from the title, including the scores for cutscenes. The former was a distinctly mixed bag, due to the tracks themselves. The main theme ‘Open Your Heart’ has a considerable amount of nostalgia behind it, but is actually one of the weaker compositions from Jun Senoue’s ‘Crush 40’ band, which he formed specifically to furnish the Sonic series with the soft rock themes that have accompanied it ever since. The rest of the tracks are variable- Tails’ theme stands up quite well, while Big the Cat’s did much to sink the character. There’s no such ambivalence about the full OST ‘Digi Logic Conversation’, which is superb throughout. Senoue handled the bulk of the composing, and the score deservedly established him as the definitive Sonic musician. Despite his emphasis on rock, he’s not afraid to vary his approach where necessary, and it’s impossible to imagine the game without his work. Shortly afterwards, a remix album of the vocal tracks followed, although this third release has not been repeated for other games.

Despite the marketing hype behind the western release, which was brought to Japan under the title of Sonic Adventure International, there was actually very little difference other than the addition of an English language track. The latter wasn’t really worth the wait, however. Sonic Team had rightly regarded having their creation speaking in-game as a huge step for the character, and expended considerable effort in auditioning and casting the Japanese version of the game. This effort paid off, with the existing characters’ voices perfectly judged, and the performers in question have been retained for every game produced since. Sega of America, in contrast, took a rather more haphazard approach, with Yuji Naka blowing a gasket on learning that Sonic and Knuckles were voiced by the same actor. In fairness to the subsidiary, many vocal artists have a huge range, with much doubling up of roles in anime productions, but having the two heroes in a piece played by the same actor did seem an excessively economical approach. There are no excuses at all for the manner in which they went about the recording, with actors given single lines to perform with no context whatsoever, instead of complete scripts. This lead to some predictably poor work, with Sonic’s deadpan “Tails. Look out. You’re going to crash. Argh!” a few minutes into the game passing quickly into legend. Luckily, this mistake was learned from, with subsequent titles seeing improvements in performance due to the provision of full scripts. The english voice cast proved a little less permenant that their japanese counterparts, however, as we’ll see next week.

|

The franchise appeared to go strangely quiet for over a year after Adventure’s release, with little activity on the home system front. The only games released during this period were some handheld titles and Sonic Shuffle for the Dreamcast. The latter was a thinly disguised rip off of the Mario Party titles, with the Sonic Adventure character models pressed into service for an electronic board game. Despite some surprisingly intricate rules, the game was even duller than its inspiration, and deservedly sank without trace. More interestingly, 1999 also saw the release of the first Sonic game for non-Sega console hardware, in the form of the Neo Geo Pocket Colour’s Sonic Pocket Adventure. It’s a charming little piece, although very little original content is present, with music and level concepts drawn entirely from Sonic 2 & 3 on the Mega Drive. Despite the Sonic Team branding, the game was actually developed by Dimps, a Japanese collective of ex-Capcom staff that appears to deliberately seek a low profile, working mainly on others’ licences. SNK’s handheld is best thought of as a bumped-up eight bit system, with the game a hybrid of the early eight-bit Sonics and their big brothers. Interestingly, the swipes from the Mega Drive’s art direction sit side by side with post-Adventure features such as the remodelled Sonic. Dimps have been responsible for the bulk of handheld Sonic titles ever since, being commissioned almost immediately to develop Sonic Advance for Nintendo’s new handheld, as an early indication of Sega’s multiformat strategy. The game was most similar to the original 16 Bit Sonic title, with the hedgehog, Tails, Knuckles or Amy having to make their way through six stages in the generic 2D style. Taking possession of the Chaos Emeralds from a skyboarding special stage offered access to the final level, but the bland level design and uninspired concepts gave early warnings that Dimps’ output would not hold much interest for those how had experienced to more inspired original 2D games. The game was released in 2001, with a port to ill-fated clusterfuck the Nokia N-Gage following a couple of years later, in accordance with Sega’s enthusiasm for doomed systems.

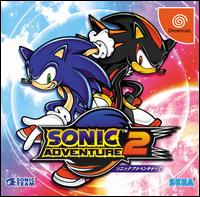

With Sonic Team proper becoming almost entirely engrossed in the development of Phatasy Star Online, the decision was taken to form a separate team to handle the continuation of their trademark franchise. After years at the forefront of the team’s games design, Takashi Iizuka was placed in charge of the new organisation, accompanied by several series veterans and the figures who had just completed localisation duties on Sonic Adventure. Yuji Naka felt that adopting a more American style and art direction would be beneficial in securing Sonic’s popularity globally, and so the developer was based in that country with the unofficial moniker of “Sonic Team USA” (their games were only ever released under the more general Sonic Team branding). Accordingly, the team decided to set the game in San Francisco, with a much more vivid style of art direction. This set-up would produce the first three games of the four installments that constituted the ‘second wave’ of the core series.

|

As with the original title, Sonic Adventure 2 focussed on a new weapon that Dr Robotnik has uncovered and was seeking to use against the world. Rather than the semi-mystical Chaos, the focus of the plot was an artificial life form created by the scientist’s grandfather, known as Shadow the Hedgehog. Claiming to be about to offer Robotnik his wish, the black Hedgehog instructs him to gather the Chaos Emeralds at the abandoned ARK space station that used to be his home. As the game progresses, however, it emerges that Shadow is following the orders of his late creator, who went mad and decided to destroy the world. In the final battle, all sides team up in the Nintendo style to counter the external threat of ARK’s computer and the Shadow prototype it unleashes. Importantly, Shadow was not conceived as a recurring character, being killed off at the close of the game. The other introduction in the game was that of Rouge the Bat, a jewel thief whose abilities mimicked those of Knuckles- this was required due to the game’s duality design concept. Adventure 2 also makes a surprisingly large contribution to fleshing out the games’ world, establishing a structure of government based around a president (who has since made a number of appearances in the series) and introducing the forces of GUN. This military organisation has become effectively the Sonicverse’s UNIT, with the force being the conventional response of society to the threat posed by Robotnik and the like. Given that half the game is played from the side of the villains and the initial arc of the Hero story has Sonic being pursued for Shadow’s crimes, the Guardian Units of Nations’ assault droids are the standard enemy faced throughout the title, far outnumbering the uses of badniks as in-level opposition.

|

The main theme of the game was a split between the forces of good and evil, with both options selectable to allow both perspectives on the story to be viewed. The “Hero” side was fill by the predictable trio of Sonic, Tails and Knuckles (with a non-playable Amy tagging along), while the “Dark” crew consisted of Shadow, Robotnik and Rouge. The Knuckles/Rouge stages were custom-designed treasure hunting areas, and stand up superbly today thanks to their non-linear construction (Pumpkin Hill is an all-time classic). The Robotnik/Tails stages reprise E-102’s shooting sections, with the fox aboard a transforming biplane mech walker. For the most part these are the titles’ weakest element, with the concept only making good on its potential in Robotnik’s final level. Cosmic Wall marked out by the genuine sense of carnage as the scientist blasts his way through ARK’s defenses, aided by some truely inspired BGM. The main gameplay addition to the Sonic stages was grinding, resulting in a tie-in promotion with Soap Shoes, which the hedgehog duly sported throughout the game. The grinding model in Adventure 2 is slightly more complex than in subsequent games, with momentum and the direction in which Sonic is leaning having an impact on his progress. The gameplay element was mainly introduced to give variety to Sonic’s progression, instead of having him continually running down narrow speedways. It’s been a mixed blessing for the series, shaking up action stages, but giving a somewhat lazy way for developers to construct a challenging level, by simply devising an area full of girders which must be jumped between with split-second timing.

The brasher feel is immediately obvious, both in the vividly sun-drenched stages and Jun Seoune’s more forthright soundtrack. To underline the fact that the game was a direct sequel, Senoue remixed and rerecorded Adventure’s various jingles (e.g. invincibility), although the remainder of the soundtrack was entirely new, with Fumie Kumatani amongst others supporting the lead composer to give each character’s stages their own shared identity. As was becoming standard, a complete soundtrack and a vocal songs album followed the game’s release. Although Adventure 2’s more linear ethos meant it fell slightly short of the original game’s high standards, it was still a high quality effort, although a weak port to the Gamecube took some of the gloss off it.

Next Time: Well, that was quite a bit of ground covered, wasn’t it? In the next instalment, we’ll be looking at the rather good Sonic X and the rather poor Sonic Heroes.

About this entry

- By Julian Hazeldine

- Posted on Sunday, July 26 2009 @ 7:15 pm

- Categorised in Games, Analysis

- Tagged with sonic the hedgehog, Sonic Adventures, Sega

- 1 comment

You’re going to include some *POSITIVE* Sonic X reviews?!

FINALLY! Someone else who likes it! :D

By Mjn Seifer

July 31, 2009 @ 9:04 pm

reply / #